Rebels the world over draw inspiration from the American Revolution. It doesn’t just inspire; some cite it to justify violence. Unfortunately, revolutions rarely compare well with 1776.

Firstly, the Founding Fathers arrived at war only after years of attempting reconciliation. After two assemblies of the Continental Congress, America’s duly appointed representatives took the decision to revolt. It was not an easy decision.

The first Congress ended with a petition to the Crown for a peaceful resolution:

Permit us then, most gracious Sovereign, in the name of all your faithful People in America, with the utmost humility, to implore you...for your glory, which can be advanced only by rendering your subjects happy, and keeping them united; for the interests of your family depending on an adherence to the principles that enthroned it; for the safety and welfare of your Kingdoms and Dominions, threatened with almost unavoidable dangers and distresses, that your Majesty, as the loving Father of your whole People, connected by the same bands of Law, Loyalty, Faith, and Blood, though dwelling in various countries, will not suffer the transcendent relation formed by these ties to be farther violated, in uncertain expectation of effects, that, if attained, never can compensate for the calamities through which they must be gained. We therefore most earnestly beseech your Majesty, that your Royal authority and interposition may be used for our relief, and that a gracious Answer may be given to this Petition.

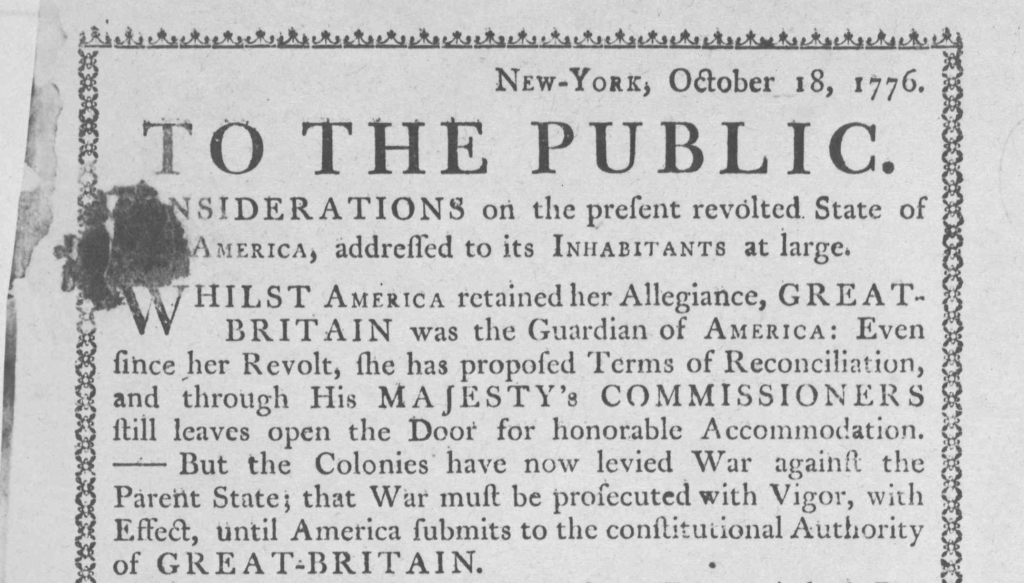

After this and subsequent efforts were rejected, the consensus for war was resolved on both sides. It’s important to remember that the colonies had legitimate militias and were constituted as legal entities within the British Empire. This was not chaos: the Patriots and the Crown agreed to solve the issue on the battlefield in a clearly prescribed format. In that respect, it wasn’t even a revolution; it was a war between well-established and governed powers with legitimate mandates from the populace. Importantly too, the war proceeded according to well-defined rules. It had limits.

Edmund Burke, in his magnificent appeal to Parliament to make concessions and preserve the peace, pointed out to his fellow Englishmen a critical point that also makes the American Revolution a poor role model for would be revolutionaries: the Atlantic Ocean. The desire of the Americans for autonomy, he says, “is not merely moral, but laid deep in the natural constitution of things. Three thousand miles of ocean lie between you and them. No contrivance can prevent the effect of this distance in weakening government. Seas roll and months pass between the order and the execution; and the want of a speedy explanation of a single point is enough to defeat a whole system….”

This is not an insurgency nor a domestic revolt as England experienced with Cromwell. It is a largely separate and already enfranchised world power deciding to settle for good the right of a remote king to control and exploit it.

As natural as creating autonomy was, Burke’s appeal also makes clear that war was still not the best way to achieve it. He argued the same end could be achieved peacefully and that the Crown could thereby preserve its interests. The Colonists certainly agreed, trying for many years to come to peaceful terms. Their efforts were capped by the last-ditch Olive Branch Petition, which the Continental Congress adopted in July 1775.

Prior to that, Ben Franklin worked hard with Burke and others to forestall conflict. “Benjamin Franklin made two missions to London prior to the Revolution; the first from 1757 to 1762, the second from 1764 to 1775. In the final four months of his second mission he became involved in three efforts to secure a peaceful solution to the constitutional divergence that was growing between England and her American colonies.” Read here this overview of Benjamin Franklin’s efforts to secure reconciliation.

Burke’s final appeal to the Crown is must reading for anyone interested in conflict and peace:

“The proposition is peace. Not peace through the medium of war, not peace to be hunted through the labyrinth of intricate and endless negotiations, not peace to arise out of universal discord. It is simple peace, sought in its natural course and in its ordinary haunts. It is peace sought in the spirit of peace, and laid in principles purely pacific. I propose, by removing the ground of the difference and by restoring the former unsuspecting confidence of the colonies in the mother country, to give permanent satisfaction to your people — and (far from a scheme of ruling by discord) to reconcile them to each other in the same act and by the bond of the very same interest which reconciles them to British government.”

Burke prescribed several practical steps:

- Allow the American colonists to elect their own representatives, settling the dispute about taxation without representation.

- The Crown must acknowledge wrongdoing and apologise for grievances caused.

- Procure an efficient manner of choosing and sending delegates.

- Set up a General Assembly in America itself, with powers to regulate taxes.

- Stop gathering taxes by imposition (or law) and start gathering them only when they are needed.

- Grant needed aid to the colonies.

Read more on Burke and Franklin.

Of course, the efforts failed. The war ran its course. But the new establishment was not a revolutionary one. The Founding Fathers remained deeply suspicious of utopian ideals, rejecting the ideas of Thomas Paine who went on to fan the flames of true revolution in France. Instead, the United States was designed according to principles skeptical of power. The leadership was reluctant to believe in grand utopian narratives, and explicitly warned of the dangers of ignorant majoritarianism. In this respect, it was most unlike other examples of revolution that leap to mind. (Compare, for example the American experience with the bloody French Revolution or the more recent Iranian Revolution, or those of the Bolsheviks or Maoists.)

Images Courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1. Illus. in AP101.P7 1902 (Case X) [P&P] 2. Portfolio 109, Folder 26 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/rbpe.10902600.