Israel’s assassination last September of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah was a turning point for the Middle East. Nasrallah was the face of the Islamic Republic’s projection of power. He was the man who defied Israel and got away with it. And he was the leader who kept Bashar al-Assad in power, proving that America’s will in the Middle East can be defeated.

Nasrallah thus embodied Iran’s Axis of Resistance and gave it life. To be sure, the Axis has other satellites, including Yemen’s Houthis and the Iranian-backed militias that dominate Iraq. But Nasrallah’s Hezbollah was the soul of it and Syria its heart. It was Assad’s Syria that hosted Iranian weapons factories, militia bases, missile sites and more—it was the arsenal and logistical supply line in Iran’s existential war against Israel and the Great Satan of the United States. And to be clear, Hezbollah was Assad’s true army.

REACTIONS AND BAKLAVA

The first reaction to the news of his death was disbelief. Nasrallah was thought to be unassailable. He led a life in hiding, was rarely seen in public, and was constantly changing locations. When the news reached me, I didn’t believe it either. Could Israel really have known exactly where he was. Well, yes, they could. And they could target a bomb to a pinpoint—not just the building, but where in the building to minimise collateral damage.

As the news sank in, my attention turned to reactions from the Arab street (which by coincidence was the street outside my window). What would they do? Should I be more careful? Should I go out? Inside my window I had the international news to tell me what they heard, and they reported nothing but denunciations: Hamas condemned the killing as a “cowardly, terrorist act.” Palestinian president Abbas deplored the “brutal Israeli aggression.” Iraq’s Prime Minister called the attack “shameful” and “a crime that shows the Zionist entity has crossed all the red lines.” Lebanon’s feckless leaders disingenuously announced days of mandatory mourning.

What will they say in my neighbourhood? I didn’t have to wait long. Within an hour I heard a very different report from what the international media shared. It was the sound of Syrians in the throes of celebration, and to emphasise the sweetness of the delightful news, they shared baklava.

DÉJÀ VU AND IRONIES

Asking about it casually the next day, I got no confessions, just knowing nods and smiles—in these parts it’s best not to discuss such things in the daylight. Someone reminded me, however, of Iranian President Raisi’s helicopter crash only five months before. That was another occasion when Syrians passed around celebratory baklava.

Israel was (probably) not involved in that, a crash that may truly have been an accident. What’s certain is that the Syrians weren’t alone in celebrating: Raisi was an exceptionally misanthropic person, responsible for the torture and deaths of Iranian protestors, Kurdish nationalists, and beer drinkers—not to mention women who dared to show their hair in public.

So, oddly, Raisi’s death united atheist Kurds, freedom-loving women, gays, alcoholics and Iranian democrats with the severe and modernity-averse Syrian jihadists of my acquaintance. And yet, the Syrian jihadists didn’t have family in Iran persecuted by Raisi, and on most counts, they shared a common outlook with him—they too denounced beer drinkers and the provocations of women’s hair.

So, what was their beef with the Iranian president? It was simply Iran’s financial and military defence of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad—archfoe of the Muslim Brotherhood and its jihadi offshoots. If not for Iran, the jihadists would have defeated Assad a decade ago.

Of course, Raisi’s demise was not universally celebrated. For example, America’s ambassador to the UN stood humbly for a minute of mourning as the United States expressed its official condolences for President Raisi’s death.

SOMETHING WAS AFOOT

Looking back to Raisi’s crash the day after Nasrallah’s assassination, I could reflect on the summer and see that as Israel methodically took Hezbollah to pieces bit by bit, the Syrian jihadist rebels and their Turkish backers were already puzzling over the new geopolitical equation.

Indeed, I’d had a whiff of it in the days before Nasrallah’s assassination. My colleagues and I noticed odd things going on in the neighbourhoods where we worked. Something was afoot: groups of serious (and seriously bearded) young Syrian men were gathering at stealthy meetings. Clearly, they were organising, planning and plotting something. But what?

At the time, we suspected it might have to do with the Turkish president, Erdoğan. Everyone knew that Erdoğan and his intelligence services backed the Syrian rebels. Was he going to utilize them domestically in case of an electoral loss?

That was one possibility, but there were other clues. The Turkish government was also unexpectedly reaching out to Assad, pushing him hard to come to the table for talks. There was an urgency to it. But why?

Then we understood. Seeing Hezbollah’s demise—the decimation of Assad’s most effective ground force—the jihadists immediately began planning their offensive against Aleppo. It was in the works all summer long. The push to bring Assad to the table stemmed from an assumption of some degree of success; odds were good that with Hezbollah’s weakness, Assad would at the very least be forced to make a deal. Of course, as it happens, no deal was needed; the offensive was wildly successful. Damascus and Assad fell to the Islamists.

TONGUES AND NATIONS

Now we have a new Syria. Clearly, Turkey is the key power. Turkey’s officials armed and trained the conquerors. Syria’s new foreign minister speaks fluent Turkish and has an Istanbul University education in political science and international relations. All the present leadership have deep ties with Turkey’s internal intelligence services.

We can expect the new Syria to be rebuilt in Turkey’s image. Turkey will reconstruct the infrastructure and will re-fashion the bureaucracy, training everyone from the police to the nurses to the agricultural specialists. Turkey will all but write Syria’s new constitution too, and its military will be virtually one with Syria’s. The new Syrian president Mr. al-Sharaa speaks openly of the Ottoman legacy that bonds the two modern states under a higher power—Islam.

All that is clear

TRIBES, TONGUES, AND NATIONS

Will it work? Perhaps, but Syria has many tribes. There are Kurds and Arabs and Turkmen. And among the Kurds and Arabs there are different faiths—Muslims, Yezidis, Alawites, Christians, Druze and “Apoists” (Kurdish adherents of the atheist-collectivist-pseudo-anarchist cult of Abdullah Öcalan). There are also Christian Armenians and Assyrians who are neither Arab nor Kurdish.

All of this is a challenge to the idea of “Syria,” a state whose identity is weaker than any of these tribal and religious identities. So as we try to understand the situation, let’s take time to review the disposition and origin of the idea of Syria as a unified state. It won’t take long, because it’s a very short history.

SYRIA, YOU SAY?

As you know, prior to the First World War, there were no nation-states in the Levant. There were no sovereign countries called Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine or Jordan. Neither was there an Iraq or Saudi Arabia. The Ottoman Empire, the Islamic Caliphate, had ruled the region as a single borderless dominion for centuries.

Israel was last a sovereign kingdom in pre-Roman antiquity, while Palestine, Syria and Iraq never were. Those names designated administrative regions in various empires from time to time, but never more than that. As for Jordan and Saudi Arabia, they were never even so much as that. Apart from Israel, none had a national identity associated with these names.

That only changed during the First World War when Lawrence of Arabia made an alliance with the Sharif of Mecca. In that deal, Britian recruited the Sharif and his clan to fight the Ottomans with the promise of an Arab kingdom at the end of the war. The timing coincided with a brand new ideal capturing the global zeitgeist: ethnic affinity based nation-states.

A deal’s a deal, and so when the war was over and the Ottoman Caliphate was broken, Sharif Hussein’s son Faisal was made king of the newly created country Syria (and his brother Abdullah was made King of the freshly minted and never-before-heard-of Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan).

THE BEST LAID PLANS

But things didn’t work out as planned: The French had ties to the Mediterranean Levantine regions dating back to the First Crusade. Now, after the long suffering of the war, they wanted these urbane coastal domains as their piece of the victor’s pie—and that included their historic hub cities of Beirut, Damascus and Aleppo. Britain could have the lands to the east and south where they could assign kings as they wished.

With Britian agreeing to the French plan, King Faisal found his reign as Syria’s king to be a brief one. With a stiff upper lip, London deftly switched him over—as if there was nothing odd about it—and appointed him the king of yet another newly created country, Iraq. And there ends Faisal’s role in our story, which although just as important, no longer involves Syria.

Sticking with our Damascene timeline then, we continue with the post-Faisal French Mandate, which began in 1922. It was a federal system made up of Aleppo, Damascus, an Alawite state, a Druze state and Antioch-Alexandretta (modern-day Hatay Province in Turkey).

With the secession of the Alawite state from the federation, the remaining elements—still under French rule—coalesced into the first Syrian unified state. The new state itself was then plagued by revolts against the French, leading at last to the nominally independent but still French-controlled Syrian Republic by 1934.

That’s the start of Syria as we know it.

BUT WAIT! THERE’S MORE!

Rember Antioch-Alexandretta? This was the northern coastal area west of Aleppo and was part of the original federation. Under Turkish pressure, French Mandate Syria relinquished it, making it an independent state. Nine months later, in June 1939, Turkey annexed it. (Indian Jones and the Last Crusade fans will recall Indy at the Alexandretta train station during the interregnum.)

Obviously, that’s important to know because of the current relationship between Turkey and its new baby, the freshly liberated Syrian Republic.

To round off the story, eventually the French left (1946) and the Syrian Republic went through a few further iterations, culminating in the ascent of pan-Arabist Baathist governments and eventually the rule of Hafez al-Assad in 1971.

WHAT DICTATORS ARE GOOD FOR

The moral of this story: Syria has never been a stable and free country with a cohesive national identity. Apart from the Druze, Alawite, Kurdish, Arab, Yezidi and Christian identities, I’d argue that another separate affinity group exists among the Damascene, Aleppine and Ladhqani cosmopolitans whose culture and values are so very different from the Islamists now in power. These are westernised, secular and “modern” people. They will have a hard time with the new rulers.

Can it all hold together? Maybe. Syrian national identity was stable for the most part during the long years of brute force dictatorship. And this was also true of Iraq, which was cohesive and stable only under the totalitarian and cruel hand of Saddam Hussein. So these were not so much “Syria” and “Iraq” as they were “Assadistan” and “Saddamistan.”

Stability is what dictatorships are good for, but it helps if they are secular and self-serving. It tends not to work as well when the dictator has a favourite dog in the race.

For example, Assad, though an Alawite, could plausibly affect neutrality because he was not by any stretch of the imagination religious—all understood that his motivation was secularly self-serving and that even an Alawite who threatened his personal interests faced the severist repercussions. Under Assad, Syria was Assad and Assad was Syria. There was no concession to Alawite nationalist ambitions.

CALIPHATES TOO

There is another paradigm for tribes getting along, however. Prior to the First World War these diverse tribes and identities lived in peace under the overarching identity of the Ottoman Caliphate. Being a theocracy, God was the authority. This certainly was not a modern “national identity” but rather a larger authority that equalised all the constituent identities under its domain, much like a dictatorship does. Here there is a favoured dog, however—Islam. It worked because its antecedent empires had a lot of practice and historical wisdom. Not yet influenced by notions of self-determination, the subject peoples likewise benefited from a historic understanding of what their role was as subjects.

Today, political Islam wants that caliphate restored. The Muslim Brotherhood, al-Qaeda, the Islamic State, and any number of other organised Islamic political and military movements—including the theocracy of the Islamic Republic of Iran and Turkey’s president Erdoğan—all seek this in some form.

To be clear, an actual caliph may not be necessary. Countries with Sunni Islamist rulers can easily play the game of nation-states for the world’s benefit and still create a common theocratic culture. Presently, that is exactly the development we see in Turkey and Syria.

ANTECEDANTS

Considering the chaos of western influence since World War One, I can agree that their argument makes sense. Under the caliphate, the disorder and violence of modern secular and ethnic nationalism was not a problem—the Islamists’ vision of peace through submission to Islam is completely rational.

This begs the question: What was before the Islamic caliphates (of which the Ottomans were the last iteration)?

To answer that, we can sketch a timeline stretching back to prehistory. It’s really a pretty simple picture:

- The predecessor of all the Islamic Caliphates was the Christian Byzantine Empire, on which the Caliphates were modelled. (While Islam’s religion was mostly modelled on Jewish literature, its political elements came from the state-based Christianity of the Byzantines).

- The Byzantine Empire was in turn an extension of the Roman Empire.

- The Roman Empire was built on the Macedonian Empire and its successor Hellenists.

- The Hellenistic and Macedonian Empires were built on the Mesopotamian Empires.

And before that? There were no empires!

Our previous posts (and book) discuss those empires and prehistory in detail. We can add to that discussion here by specifically looking at it in terms of tribes and peoples—ethnic and national identities.

And that’s exactly what we will do in the next post. Look for it in the next few weeks. At the end of the story I’ll reflect more on what it all means for Syria, and what it means for us.

Stay tuned….

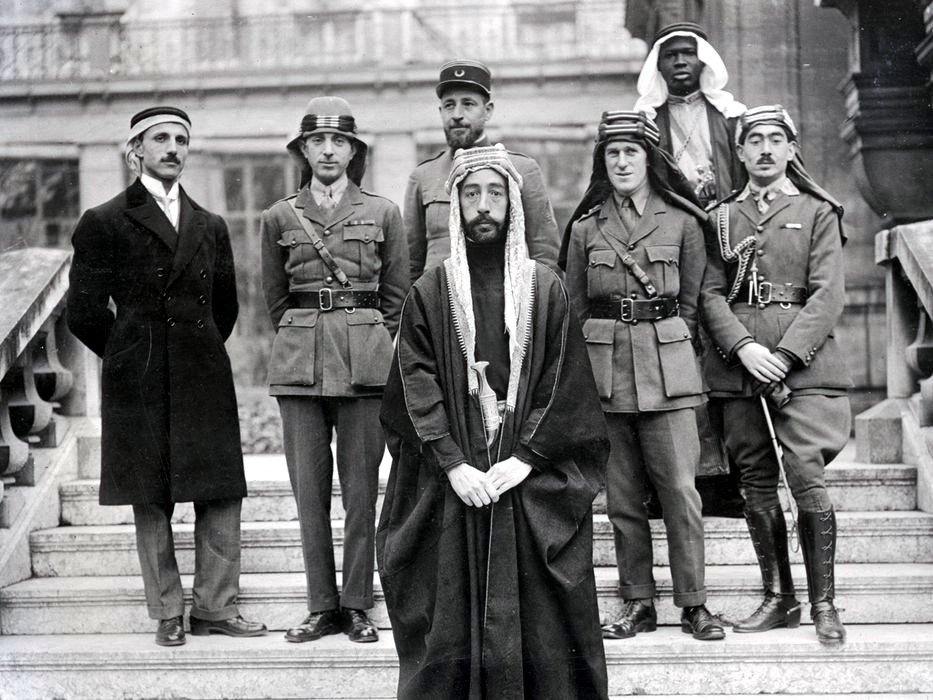

IMAGE: King Faisal. Lawrence of Arabia stands behind him, immediate right.

A FOOTNOTE: ON ISRAELI AND SYRIAN TERRORIST HEADS OF STATE

Syria’s new president and reformed terrorist Ahmed al-Sharaa has something in common with Menachem Begin. The international community designated Begin a terrorist for blowing up the Kind David Hotel and killing British servicemen. Later he became prime minister of Israel and signed the Camp David Accords making peace between Egypt and Israel.