My book discusses the development of civilisation and government, empire and warfare, economics and materialism. Our sources were civilisation’s own histories and myths and the parallel criticism of it delivered by the Hebrew tradition. In these posts, I have reiterated some of those themes.

Now I would like to filter that discussion through the lens of ethnicity, nationalism, tribalism, borders and identities. Our goal is to understand more about what this means for the Middle East, and what it means for Syria in particular. And who knows, the discussion may by and by illuminate some of our tribal domestic tensions too.

LINGUA FRANCAS AND MEDIATED EXCHANGES

As their own histories attest, when the first city-states consolidated into the Babylonian (Akkadian) Empire some 4,000 years ago, they gobbled up tribes and peoples and languages.

Homogenization followed, born of the central mediation of the imperial authority. Lingua franca gave the tribes a mediating single language—the only language that had power. Currency mediated exchanges of goods, such that those who once took care of each other’s material needs within a community now found money standing between them. Paradoxically, this also made completely non-relational exchanges possible between those who before then had no contact whatsoever. Mediation and commodification are central to this great revolution in the way humans live.

While homogenization by virtue of a state and national identity characterises early empire, these entities were not like modern nation-states. There are similarities of course—both absorb their constituents, for example. But the nation-state is different in so far as it imposes a single ethno-linguistic identity on all its citizens. The nation-state idea, which only appears in the late 1800s, is a process of fragmentation into narrower uniformly monotoned sovereign realms. The original states of civilisation’s early empire did not do this. Rather, they aggregated peoples under a larger umbrella, the identity of which was the deified state itself.

THE TURKISH MOTHER TONGUE

To understand the difference, consider Turkey, a classic example of the modern nation-state.

Turkey became such a state in 1923 after the forced dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Its constitution defined all Turkish citizens as ethnic Turks, and the nation’s mother tongue as Turkish, a truly proscriptive regime of assimilation that most dramatically affected people whose mothers unfortunately spoke another language, for example, Kurdish.

Although today it carries the force of natural law, feeling as though any other option is morally suspect and strange, I must stress that this is a very new idea. As it caught on as a revolutionary concept in the late 1800s, the nation-state ideal summoned into existence a new sacred tenet, the “right to autonomy” by which every ethnicity and affinity group may claim its own independent state. Not to have one is to be a victim. Getting one sanctified any action, to the point that its acquisition justified the shedding of blood and even terrorism.

In contrast with “Turkey” consider its predecessor, the Ottoman Empire. Like its own imperial precursors, it was not built on a single ethnic identity. And as with all empires, its peoples and tribes lived in an autonomous equilibrium of subjugation to the imperial ethos. To be a Kurd, or Turk, or Persian, or Armenian, or Jew in the Ottoman realm was fine.

Under the empire, each group spoke its own tongue and practiced its own rites. The empire itself, however, had a language all its own, an overarching one that unified and pacified the diverse tribes under its heavily enforced dominion. This overarching character of empire allowed for traditional ethnolinguistic identity and customs to remain intact, even if subjugated. This is not true in modern nation-states. They are monoethnic and play a zero-sum, all or nothing game. Just as ask any Kurd in Turkey. (To be clear this is no longer the case due to the neo-Ottoman vision of Turkey’s current president! More on that later….)

WHENCE TRIBES AND TONGUES

Of course, empire was far from ideal. It promised, and for the most part guaranteed, stability and peace between the tribes. But it was brutally coercive and exploitative. Ethnic peoples and tribes submerged their identities under that of the overarching empire. In this, the empires of old resemble the recent dictatorships of Syria and Iraq. Both ensured domestic peace and stability, notably affording protection to minorities like Christians. For those who lived their lives without offending the state apparatus, life was unruffled. Those with ideologies that conflicted with the overarching one, however, were in for a world of pain.

Indeed, twentieth century dictatorship and old empire are analogous. Clearly both can be awful. Freedom is limited, and punishment severe. But what is the alternative? Is it to promise everyone a nation-state and let them fight over the land? So far in Syria and Iraq, the substitute for empire and dictatorship is dozens of factions at war to the ruin of families—women and children—by the hundreds of thousands. The largest minority—Christians—ended up decimated through the struggle. Are these our choices? Bloody anarchy or ethnically cleansed nation-states on the one hand, or the brutal subjugation of dictators and emperors on the other? Had you the misfortune of being born there, which would you choose?

The authors of the Hebrew Scriptures envisioned a true alternative. Though many in our age dismiss it as an anthology of fairy tales, to do so signifies ignorance. Remember, the Hebrew tradition arose alongside the advent of the first states. At its heart, the Bible is a sociological critique of Mesopotamia’s civilisational model—the model that we still subscribe to. It’s important. It’s relevant.

The beginning of that critique is the Genesis story of the Tower of Babel.

SERIOUSLY?

Like much in the Bible, the Tower of Babel has a credibility problem. Maybe its relegation to cartoon-like treatments in Sunday school are at fault. But this certainly is not a cartoon or a fairytale. It is a profoundly poetic description of the founding of the world’s first political systems, and it is alarmingly accurate. This is history. And this is a warning about civilisation at its inception, a text of penetrating, eviscerating insight.

I do not mean that it is a documentary chronical, however. To set down in detail the history that this passage represents would require many volumes of text and a lifetime of study. Some of us have done that, and it only makes us appreciate Genesis even more, because truth in history is not always well served by litanies of factual detail among which we easily miss the forest for the trees. The history of Genesis is powerful because it is so condensed, a distillate of a complex and lengthy process that can be grasped instantly thanks to the efficiency of the biblical algorithm.

ACCURATE TOO

It is also accurate in the details it provides. When Genesis names the first hierarchical states as Erech and Babel it gets the facts right. It’s hard to overestimate what this means—Erech really is the place that invented the modern world. It is incontestably the first ancient Mesopotamian city-state.

Today, Erech (אֶ֖רֶךְ in Hebrew) is usually transliterated “Uruk” to match its written Akkadian Empire form, but rest assured, Erech and Uruk refer to the same place. How can we be so sure? It’s pretty simple. We possess a continuous chain of references documenting the mutations of the written form across several millennia. This is no different from what happens when we write Jerusalem in English for the Hebrew word Yerushalayim, which ancient cuneiform texts wrote as Úrušalim—I mean it is exactly a parallel example. If we’d only just excavated a previously undiscovered Jerusalem, a city known to us only as Yerushalayim from a reference in the Hebrew Bible, and there discovered its name on cuneiform tablets, we might well refer to it regularly today as Urusalim.

As it happens with Erech, scholars comfortably use both forms. For example, Samuel Noah Kramer consistently used Erech in his writings. He is the father of modern Sumerian studies, the man who originally translated this city’s oldest texts.

Remarkably then, Genesis rightly reported what archaeology only discovered in the twentieth century—that this city is indeed the beginning of kingdoms on earth. To underscore the point: this is the world’s first city-state, the prototype of government, originator of writing, taxes, armies and schools—it is the cornerstone of civilisation. It’s even why there are 60 minutes in an hour. (Intrigued? Read more about it in my book.)

OF BABEL AND KINGS

Genesis also talks about the founder of these cities and civilisation. It was Nimrod, “the first on earth to become a mighty warrior.” His name is representative, mythological. Nimrod is the archetype of all dictators, emperors and governors, and in Genesis, he is the inventor of kingdoms and thus the first king. His mention here in Genesis parallels Mesopotamia’s equally symbolic lore about the first king, which speaks of a watershed moment, the before and after of civilisation’s dawn. “After the kingship descended from heaven, the kingship was in Eridu.”

Now, this city, “Eridu” is Erech’s close associate in the biblical text, which calls it by its more familiar name, Babel. We can firmly link Babel with Eridu because that’s exactly how the locals referred to it. Although formally called Eridu, the Sumerians honorifically referred to it as Babel. Actually, it is the first and original of many Sumerian cities that would be referred to as “Babel” over the next several millennia—the appellation migrated to cities that became especially important, such as the capital city of the empire.

AND TOWERS AND TEMPLES c. 4000 BC

Very importantly, this (literally) genesis city was the spiritual reference point for the first empires, given credit for shaping the founding culture’s cosmology. It was thus the template of civilisation’s ethos, and again, it was the place that “kingship” first appeared on earth. This is true in fact and in Mesopotamian and Hebrew lore. Modern archaeology, Sumerian mythology, and the Bible all credit Eridu/Babel with devising government and kingdom and everything that goes with it.

This is where the Tower of Babel comes in. It was this very city that invented the urban temple. And I mean just that: it set the type that every other ancient civilisation follows right up through the Romans and from there, on into the design and placement of church cathedrals, mosques and myriad Far Eastern counterparts. And as you’ve guessed, its original form was a tower.

We know this because archaeologists excavated the city in the mid-twentieth century. There, they found the remains of the Sumeria’s oldest discovered temple, a site that also holds the record for the longest continuous use of a temple structure, which saw uninterrupted service for a staggering 2,000 years and boasted seventeen different layers of construction, one on top of the other.

Yes, that makes it a tower—a literal tower of babel. The Mesopotamians called them ziggurats: 𒅆𒂍𒉪 a word formed from “build high” and “reaching heights,” attributes that Genesis pointedly echoes.

ANOTHER GENESIS

I may as well mention that the Mesopotamians had their own Book of Genesis. Thorkild Jacobsen, who first translated it in 1939, summarises the plot:

In the Eridu Genesis…the wretched state of natural man touches the motherly heart of [goddess] Nintur, who has him improve his lot by settling down in cities and building temples; and she gives him a king to lead and organize.

Sound familiar? Here is a quote directly from the text, where the goddess explains her rationale and plan:

Let me bethink myself of my humankind, all forgotten as they are…. Let me bring them back from their trails. May they come and build cities and cult-places [ziggurats] …. May they lay the bricks for the cult-cities in pure spots, and may they found places for divination… Let me institute peace there.

Mesopotamia’s understanding of humanity’s situation was that it was benighted because it was disorganised. This was a revolutionary renunciation of the still quite recent hunter-gatherer past, a way of living that characterised fully modern humans stretching back a hundred thousand years.

It’s important to understand that we cannot infer from ‘hunter-gatherer’ an undomiciled or in any sense primitive people. From 10,000 BCE, hunter-gatherers in the Near East lived in large egalitarian towns, produced art, built comfortable homes, and supplemented their completely equitable hunter-gatherer diets with a small measure of modestly cultivated wheat. What made them different from us is that they had no hierarchy, expansionist ambitions, or any of the accoutrements of a marshalled society. Comfortable stability describes the situation well.

ANOTHER PERSPECTIVE

Of course, Hebrew Genesis presents the original ethos of the Sumerians much as the Sumerians described it. Both talk about the first king and a plan to bring people together in the first city-states, ordering individuals and disparate nomads into a super-corporate identity.

We could say much, much more about shepherding hunter-gatherers into city-states and the concurrent advent of kings, but we must limit our discussion to tribes and nations. To that point, Hebrew Genesis gets right to the issue in its preamble to the Tower story, telling us that the world is in trouble because “the whole earth had one language and the same words.”

BABEL’S VERSION

It should be clear that the Mesopotamians start from an earlier point, describing humanity before kings and the city-states. Indeed, the text aptly references hunter-gatherers, which is why the goddess wanted to bring the peoples from “their trails” and pledged to save them by establishing “cities and building temples” and providing “a king to lead and organize.”

That’s not all it says, though. Babel’s Genesis specifically denounces humanity’s scattered tribal disposition as a flaw. The human condition before the divine intervention of bringing a king and city-state is disparagingly that of “the many-tongued.”

For this too, it has a cure, calling them “to come together…in a single language!” Further to the point, it links this process to the god of Babel’s tower: “For at that time, the lord of Eridu [Babel] shall change the speech in their mouths, as many as he had placed there, and so the speech of mankind is truly one.” The result: “the whole universe’s speech a single language.”

COME NOW!

Our Hebrew writers pick up the story right here, a point at which the Hebrew text says there is “one language and the same words.” From the Bible’s perspective, the builders’ motivation is fear—it is a stand against heaven to forestall having their global cohesion taken away:

Come-now! Let us build ourselves a city and a tower, its top in the heavens, and let us make ourselves a name, lest we be scattered over the face of all the earth!

You know what happens next. Heaven says no:

Look, they are one people and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come-now! Let us go down and let us baffle their language, that no man will understand the language of his fellow, so YHWH scattered them from there over the face of all the earth!

In Hebrew Genesis, it seems that God prefers tribes, tongues and nations and prefers people scattered in their trails.

We hardly need modern archaeology to understand that the Hebrew scripture’s purpose is to critique the culture of civilisation’s origins. But archaeology helps. With the discovery of the Mesopotamian “Genesis” in 1891, we gained a sharply direct text-to-text sharper juxtaposition of these two worldviews. Bear in mind that the archaeology of the period was part of a focused modern scientific quest to explore the foundations of civilisation. That the Bible should stand some five millennia later as such a powerful sociopolitical criticism of it should, I think, go a long way in the minds of any thoughtful person to rescuing the Bible from Sunday school irrelevancy.

NIMROD REMEMBERED

There are many others across the ages who have weighed these matters. Even without having “Eridu Genesis” available for comparison, the Hebrew/Mesopotamia tension was clear to ancient commentators.

Consider first-century Jewish-Roman historian Flavius Josephus, who wrote of civilisation-founder Nimrod that he wanted humankind to find happiness only in the materialism of the civilisation he created. Nimrod called faith in the Divine “an act of cowardice,” says Josephus.

Further, he writes that, “Nimrod persuaded them [the people] not to ascribe happiness to the Divine, as if it was through Divine means that they were happy, but to believe that it was their own courage which procured happiness.”

That’s a good summary of what civilisation attempts: to replace the lost, happy spiritual consciousness represented in Paradise with an alternate universe of discontent built by human imagination and technological innovation—self-salvation, self-worship, time-bound, constrained by the material world.

Josephus characterised Babel’s endeavours in well-chosen words, suggestive of the sterile and abusive materialism that in our modern age is the be-all and end-all of reality: “He also gradually changed the government into tyranny, seeing no other way of turning men from… the Divine, but to bring them into a constant dependence on his power.” The “his” there is Nimrod, but you might substitute “investments” “science” “politics” or anything that fills that role in your life.

MARRIED TO A TYRANT

Why did people go along with it?

Consider this. Tyranny is the process by which fear rules over us—so if one fears the power of something to give us life or take it away, that thing becomes a tyranny. So, the answer to the question is the same as it is for anyone who stays in an abusive relationship—a tyrannical relationship. We stay because of fear, low self-esteem, anxiety about losing material security, and peer pressure. Those top the bill, but many people stay in the relationship simply because they think it is normal: they’ve never seen a healthy relationship—their perspective on reality is false.

To restate our thesis: In the Hebrew and Mesopotamian origin stories we hear two very different evaluations of what Babel represents. One endorses the developments that birthed civilisation in Mesopotamia, the other denounces it.

After the Tower of Babel, the Hebrew side immediately offers a personalised version of the argument. It tells us of Abraham, a scion of Babel’s most powerful urban families. His father was enriched by Babel. The tyranny of the system bore down on the family as a threat to lose their wealth if they defied it. Abraham’s context as a man of the system is critical to grasping the meaning in his story. It is essentially a story of reversing the original Mesopotamian call. Abraham leaves it all behind—all that subtext of security—to quite literally resume life in the trails.

Thus, Abraham embodies the Hebrew criticism of civilisation’s Babylonian assumptions. And although it is not explicit in the Bible, Middle Eastern folklore among Jews and Muslims (and even pagans) recall him in this regard as the idol-smashing nemesis of none other than city-state founder, Nimrod.

THE PERSIAN VERSION

From the historical record we know how Erech and Babel progressed to create the milieu from which Abraham emerged as an iconoclast.

Those first city-states coalesced into the Babylonian Empire, of which there are several iterations, not a single dynasty. Historically (including in the Bible) you’ll read about the Akkadians, Assyrians and Neo-Babylonians. We understand from their own and others’ written histories that although these dynasties shifted through considerable bloodshed, their ethos did not change. We can say without oversimplification that Babel’s was one continuous monolithic state from the mid-3000s BCE until the mid-500s—a solid 3,000 years.

MID-500s BCE

So what happened then in the 500s BCE? In a word, Persians.

What’s essential to understand about the Persians is that prior to them every new ruling dynasty in Babylon was wholly absorbed into the original Mesopotamian worldview. Each successive dynasty legitimised its rule by connecting it to the Eridu template and that same god referenced in Eridu Genesis. New regimes never captured Babel—Babel captured them.

Thus, up until the Persian conquest in 539 BCE, every iteration of civilisation subscribed to a version of the same cosmology and culture. Cyrus, the Persian King of Kings, broke that chain. What had been until then an inevitable way of being, a matter of simply the way things were, was shattered in a single night by Cyrus.

STAGE SET

The gathering of the scattered and the scattering of the gathered; the unification of language and the confounding of tongues; all this is the stuff of nation-states. I hope this background will help us as we move into the next part of the discussion.

NEXT:

Up next…We will continue this story with how Cyrus changed human expectations forever. His influence on what we expect of society—of life itself—is astonishing. Even more astonishing to me is how little we understand about him and the role he plays in our lives.

We’ll talk all about that and look even deeper into the question of ethnic nationalism, self-determination and much, much more, leading to a final discussion of what this means for Syria and what it means for us in the ideologically tribalized West.

A FOOTNOTE: NATION-STATES AND MISSIONARIES

Oxford tells me the term nation-state first appears in the 1895. That this coincides with the missionary boom of the same era is no coincidence. For example the ecumenical World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh, held in 1910, sought to assign the “unreached peoples” of the world to the mainstream churches so that they could be evangelised.

It was all part of the progressive post-millennialist vision. A form of millenarianism, the idea was that Jesus would return after the work of reaching every tribe, tongue, people and nation was complete. A missionary’s call was to preach the transformative Gospel and to provide along with it the blessings that the Gospel brought to the West: medical care, modern education…even democracy. As there was an explicit focus on unreached ethnicities—for example, the Kurds—the missionaries preached the kingdom of God, but often with the implicit idea that god was supportive of their target ethnicity having a kingdom of their own!

A favoured text was Acts 17:22 where the Apostle Paul explains to the Athenians that ethnicity and political boundaries (the post-Babel scattering) were part of God’s plan.

So Paul, standing in the midst of the Areopagus, said: “Men of Athens, I perceive that in every way you are very religious. For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription: ‘To the unknown god.’ What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you. The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything. And he made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him.

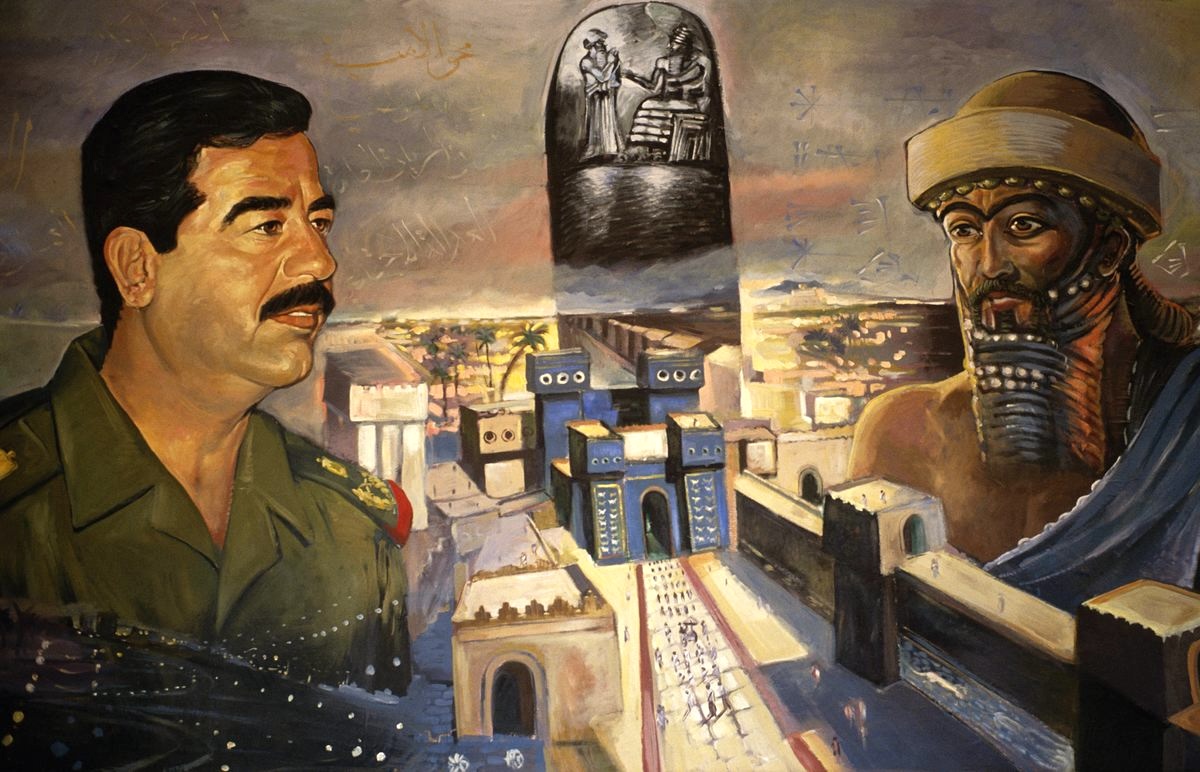

IMAGE: Saddam Hussein explicitly identified his dictatorship with that of Babylon’s Nebuchadnezzar