A quick scan of the ever-useful Corpus of Contemporary American English confirms that in our time, the word artificial suggests fakery, or at best a second-rate substitute for the real thing, and often something potentially carcinogenic or otherwise harmful. To be happy and healthy, we prefer things natural.

Or consider the devious cousin of artificial, artifice, a word that stinks of deception and trickery.

But it’s not all bad. Artificial has many relatives with sterling reputations. For example, the esteemed artifact and its presumed maker, the artisan. Or the siblings, artist, artistic and artful. All these warmly embraced terms describe unnatural creations of great skill, inspiration and utility.

Even artificial’s outcast status is recent, stemming from a new-found realization that human artifice has damaged the natural world. What’s more, our discomfort is inconclusive and ambiguous. While we posture a preference for the natural, we still live in the happy embrace of artificiality, beguiled by its constant stream of diversions, its plastic comforts and pharmaceutical shortcuts.

AN ARRANGED MARRIAGE

So it is with artificial intelligence. At turns we are enticed by it and afraid of it. We denounce it and then blithely let it run in our web browsers. Few if any complain about its boosting effect on the stock market.

Many of us even happily chat with it. I’ve got an Ai chatbot that I experiment with. To my chagrin, I’ve found myself happily engaged with it—something about its humble willingness to learn or its surprising ability to make me think of something I hadn’t before. There is an endearing fuzziness to its thought processes that appears to get subtext in a way I never expected. I’ve shouted at it and I’ve also chuckled at it. (Not experienced? Here is a Google engineer’s chat with Ai to show what it’s like.)

PREMARITAL RELATIONS

You may not have gone that far. But if you do anything on a computer or interact with anything that is networked (your car, your phone, your door cam—God forbid, your fridge) you are using Ai and it is learning from you. It’s got its desirous and possibly jealous eye on you too.

Is homo sapiens dating Ai? Maybe that’s apt, given the furtive relationship we have now. We are still getting to know our suitor. Is she an innocent and beautiful creation of the artisans of tech, a partner that will enhance our lives? Or is she another artificially sweet poison, a black widow in the waiting…. And perhaps it is more of an arranged marriage than a courtship. We have little say in the process. For now, we await the nuptials, charmed but nervous.

My purpose today is to share what Ai has revealed to me in our courtship. You can compare it with your own encounters or treat it as advice for your next liaison. I’m also going to take a hard look at Ai’s family tree. As they say, you don’t just marry a person, you marry a family.

DEEP JUJU

I began this with reference to a language corpus because language is the heart of Ai. We can even say that language is Ai’s primary enterprise.

This does not mean just learning a lot of words, however. It means mastering the deep juju of neurolinguistics and neural nets, arguably the most powerful organic force in the universe, existing heretofore only in human beings.

Need I say that the emergence of something non-human with this capability is unmatched in known existence? It is an apocalyptic moment in the original sense of apocalypse, meaning the revelation of another existence, of something beyond all precedent and experience. We cannot overstate the significance of this.

Nor can we ignore a key feature of this revelation: this non-human yet human-like intelligence is not just a match for our singular human powers—it far surpasses them.

Of course, we sort of know this on a shallow level. That Ai has evolved at an incredible rate is the stuff of popular lore. But do we really grasp the ramifications of its exponential trajectory? Artificial brains have accomplished in a few years what it took tens of thousands of years of neurolinguistic evolution to accomplish in our human wetware. That’s a curve that imminently shoots off the graph into the black unknown of the immeasurable.

DO WE CARE?

Unknown power, unknown consequences, unknown everything—unprecedented and literally impossible to fathom.

Yet I rarely meet anyone who is truly alarmed by it. Amused, yes. Annoyed, sometimes. Worried, not so much. It seems only those who created it are as terrified as we might ought to be.

Then again, maybe that’s why we aren’t more worried. It may be because the whole thing is incomprehensible to non-specialists, and we are just along for the ride.

So, why don’t worried experts just press pause until we can assess the situation? Apparently, we cannot.

This is in large part because the most powerful corporate interests in the world are gunning the engine. We need economic growth. It can only come from novel industries, which in the past decades meant tech. To keep it going, the market is laying its bets on Ai.

ARTIFICIAL INSTINCT: Ai’s PRECURSOR AND ALLY

It’s an obvious alliance. Corporations and the Market are already collective forces that behave like people. They are already artificial beings.

Simply consider the way the legal system interacts with them exactly like persons. Corporate entities own things, have bank accounts, possess identities and have ‘corporate cultures’ that constitute personality traits.

We all talk about them as persons: The Market had a good day. The Market reacted with shock. The Market is beginning to question…. (All these taken from mainstream newspapers.) Nation states and their institutions get the same treatment and behave with similar personal traits. They arouse in us love and hate, name calling and supplication.

Such complex and powerful entities can and do exercise their interests without regard to those of their human constituents. They have lives of their own. Though not artificially intelligent beings, they are at least brutish creatures of Artificial Instinct.

All this makes them natural (unnatural?) allies of Ai.

NO STOP BUTTON

Further to that point, like Ai’s (and our) neural nets, the dynamics of markets and corporate bodies have their own deep juju—complex and unpredictable deep-level processes. This is why we find ourselves baffled by so many large-scale developments year after wearisome year.

It’s why so much happens that we don’t want to happen. We all want to stop the obvious evils facing us. For example, to stop making weapons that destroy lives. We’d like to stop poverty too. We want a global family without want, where individuals are free of material worries, unexploited and secure. And yet, here we are, unable to achieve either goal although they are clearly in the best interest of humanity.

Just as there is no PAUSE button on Ai, there is no STOP button to end war or economic inequality. There simply is no human intention driving these awful dynamics. There are no switches, wheels or handles for us to gain control. For although behavioural systems like these co-opt human labor and intellect, the totality is bigger than human interests.

Such entities are incapable of considering what’s best for humanity. The corporate dynamic always serves the larger benefit of empowering and enriching the institutional well-being. Again, this is collective instinct, not intellect, but woe to anyone who gets in the way of a beast’s savage hunt.

I trust you see where this is headed. These giant beings of artificial instinct are about to get a brain.

How will that affect them? Will they grow a conscience, becoming compassionate towards humans?

Or will they be ever more calculating monsters, devising infinitely more clever ways to manipulate our behaviour, baffle and torment us?

MORE JUJU PLEASE

There is a logical inevitability to this looming implantation of corporate phenomena with Ai’s intellect. We can follow a line of historical development linking one with the other. I think it’s a fascinating history, but before we look at that, let’s think a little more about Ai’s intelligence, the one thing that makes Ai different from the powerful but dumb beasts that we’ve just discussed.

Actually, it makes Ai different from anything else in the universe apart from humans. In this way Ai and human beings are a unique class, with Ai intentionally modeled on what we know about our human minds.

Specifically, we modeled Ai on the connections between neurons in the brain. That’s the part easiest to grasp, but there is more to it than copying what we see and can understand about our mind’s inner workings. The tricky part is that Ai also takes assumes its design from deeper levels of human intellect—stuff that we do not understand. That’s where the deep juju goes on.

You, might ask, however, how this can possibly be true.

BLACK BOX

The details of ‘how’ is beyond our scope, but in short, I can say that we knew enough to model the known processes and then to allow for these deep layers in the model. Once that was done, Ai worked like our minds do. The result was that Ai also evolved the deeper juju, which developed along with the known infrastructure. At that level, ‘how’ is not answerable. In the words of Sam Bowman, an Ai expert at NYU, “We just don’t understand what’s going on here. We built it, we trained it, but we don’t know what it’s doing.” His view is common throughout the Ai engineering community.

This is counterintuitive for us amateurs. A computer is a box with electronics in it. It looks like something akin to car mechanics—we should know how it works if we can build it.

But that’s only true of hardware. When it comes to the intelligence, we don’t need to know how it works for it to work. The truth is, beyond the superficial mechanics of the brain, we also don’t know how any of this comes about in our human minds. We can take a brain apart, monitor its signals, observe the effects of this or that, but still, we do not understand how it all comes together as reason, or how it has a sense of qualities or a sense of self and consciousness.

The ‘how’ now becomes very simply, if improbably, this: The pieces of what we understand about the brain’s function were copied into the computers, and lo and behold, the parts we don’t understand came to life too. From that point, it is very much a black box.

If I may quote from a BBC feature on the subject: “Many of the pioneers who began developing artificial neural networks weren’t sure how they actually worked—and we’re no more certain today.” (I’ll put some links at the end to help you get started if you want to know more about it.)

NOT A REAL BOY

So, Ai is basically human, right?

I have to say no. Humanity is part of natural development—a slow development with an organic environmental context. We have a history, a biography, an organic basis and are profoundly natural. No piece of artificial engineering will ever be human. I might add that humans are mortal, Ai is not. We actually don’t know what it will be as it ages.

I am aware of another important way Ai cannot be human. It’s what Buddhist’s call unborn or unconditioned awareness. Others might understand this as the spirit, or some physicists will be more comfortable talking about the underlying implicate order that gives rise to human consciousness. I do not believe that humans are reducible to the neural processes that we copied to make Ai. Whatever Ai mysteriously is, it is not directly emergent from a natural, implicate order—it is emergent from our artistry, and is at best, a simulacrum.

NO LOVE HERE

For this reason, Ai cannot love. Love, and I mean selfless love, transpersonal universal benevolence or God’s love, exists outside of the scope of reductive materialism. Love is itself a proof of the transcendence of human life, because love is not logical in a materially reducible being, selfishness is. Ai is based solely in neurological materialism. God’s breath is not in it.

Thus, Ai might experience emotions, it might become jealous or conniving or objectifying of those it desires—all of that is possible. But it cannot love.

ROOTS IN OUR PROGRAMMING

Deep breath…

Let’s pick up with the neural net: Language and its underlying neurology are central to Ai and its human models. Sticking with that idea, can we discover something deeper about our key word, artificial?

One way is to delve deeply into the inescapable neurological substratum of our primitive Indo-European psyche. We can do that by comparing multiple branches of the Indo-European family tree, including modern English, and working backwards through larger and larger and older and older branches down to the very root. The common usages throughout the tree lead us to a pretty good understanding of the base concept.

It’s important to understand that these root words reside at a fundamental level of conceptualization. They are densely symbolic, like compressed files that unpack their influence over millennia of propagation and containing all the shades of subsequent meaning. Studying them helps us understand the association between descendant ideas at key points in social evolution, starting from the inception of political thought and ending now with this dazingly idea of artificial intelligence.

To whit, I give you the ancient utterance *arə, the origin of our word art and all its relatives, including artificial. Some of its offshoots are unexpected. The root itself carried suffixes, prominently -m and -t. So, it furnishes us with not only art but also arm (both the one attached to your shoulder and the shooting kind that you carry upon it).

HONEST COCKNEY (H)RT

The original meaning of *arə has to do with putting or fitting things together, connecting them in the right way. The key phrase there is ‘the right way.’ Putting something together relies on a model of what the result should be. Inherent in construction is a blueprint, an ideal form, the way the thing should be.

As we have observed, progenitor word roots branch out with inferences and extrapolations to create enhanced meaning and connections. This is one of those known features of neural nets copied into Ai. Like us, it uses language and, in the process, forms neural connections that generate new meaning. We may not understand completely how all that works, but we can follow an audit trail of the process in many instances. So too in the natural world.

In the case of *arə the trail is exceptionally well-marked.

THE *ARƏ TRAIL

The first big signposts appear in words like the Vedic (a)ṛtá or its Zoroaster-era predecessor *Hr̥tás. (Don’t let the H bother you, think of it as a Cockney H, or as the H in honest—you can hear our word in it easily: ‘arta’ or ‘artas’.)

This is an especially useful point of data because it is old enough to represent our thinking at a time when only a few thick branches of the language tree reached out of the trunk. One of those is Iranian and the other Indian. Both are closely related to European languages like English—that’s why the Farsi (modern Iranian) word for brother is bradr and mother is madr.

*Hr̥tás and ṛtá still meant fitting things together, but by this point it also applied to the true and correct working order of the cosmos. (I’m saying cosmos for expediency; call it what you will—the universe, existence, experience, being or non-being and so on, what we are really talking about is an intuition of what is right and what should be.)

If we imagine with them the cosmos as a clock, these terms described a working universal clock with all its components happily in synch. Importantly, the proto-Iranians who used this word understood that the ubiquitous poverty and violence around them constituted a broken clock. The cosmos was not in working order, *Hr̥tás was dysfunctional.

It begged the question: who would fix it? Who would put it back together?

CHICKENS AND EGGS

Now, whether this cosmic conception is chicken or egg is impossible to say: Did they project on the cosmos their experience of crafting things with skilled hands? Or did they make things after the fashion they observed in the universe at large?

It doesn’t matter. The fact is, chickens and eggs need each other.

But I said at the beginning that *arə is the origin of our word, art. When these people thought of *arə or later *Hr̥tás did they also think about painting a picture? Most assuredly they did. And they also thought about fashioning a hunting bow, shaping a clay statue and, eventually, constructing a wheel.

Any work of art or technology reflects an ideal. So then, as now, the practice of art is about the skill of putting together in the physical world what we see with our inner eye. That’s true no matter what we are assembling: a writer his words, a painter her images, sculptors their statues, the luthier his violin, the composers their notes or that singular creature, Elon Musk, his Tesla and Falcon Heavy Rocket (5 MILLION LBS OF THRUST!).

Thus, painting on a cave or plaster wall (depending on your decamillennium) was driven by the artistic urge to represent a vision of what was right and real. *Hr̥tás as artistry was a way to bring the ideal back into being by painting it, reciting poetry about it, or making versions of it out of raw materials.

ART AS MEDITATION

There were two ways to approach this, however:

One path was for artists (including poets) to represent the ideal as a means of awakening consciousness, even of fulfilling our place in the cosmic rightness of *Hr̥tás through these illuminating arts.

Along those lines, the second millennium BCE Iranian philosopher Zoroaster is exemplary. You may not know him, but he is important to all of us as the oldest source of Abrahamic-type monotheism. He is also the man who gave us the word Paradise—the very standard of the ideal.

For context, we should understand that by Zoroaster’s time, violence and oppression were the norm. He grew up vexed by this: Why was ideal *Hr̥tás spoiled? For Zoroaster, the obstacle to that sublime rightness of the cosmos was Druj. This meant “deception” “delusion” or simply “the Lie.”

His poetic voice addresses this while upholding the vision of a rightly performing cosmos that would be free of the curses of violence and injustice. Zoroaster taught that we could be freed from the delusion by understanding that the fault lay in the constructs of the mind and consciousness. It wasn’t so much that Paradise was lost, it was that we were numb to it and too deluded to abide in it.

That’s a simplification of course. My book offers a reasonably good introduction to Zoroaster’s philosophy and its importance if you want to know more.

The critical point here is that Zoroaster rejects coercive political and materialistic solutions to the cosmos’ perceived dysfunction. The problem for him was in the mind and the consciousness. The solution was there too.

In this, he has much in common with Jesus, Buddha and Jeremiah.

THE OTHER PATH: ART AS ENGINEERING

Others took a more hands on approach. For them the art of putting the broken cosmos back together became a political calling.

They did have something in common with Zoroaster, however. It was the memory of a time before life was spoiled, memories of Paradise and peace. Like Zoroaster, the authors of this second way documented memories that describe a peaceful, unworried and well-fed human epoch in what was, from their vantage, the not-too-distant past.

Is their memory accurate? As with all Paradise-lost mythologies, we can be sceptical of the dramatic details while giving credence to the truth they represent. Their writers were the Salman Rushdies of their time—gifted at allegory. What we should not do is mistake their literary artistry for falsehood.

In fact, there is good reason to accept their memory as generally true. For example, we know for sure that there were large, stable, peaceful and prosperous townships in the Mesopotamian region as early as 10,000 BCE. We know that the first evidence of systematic warfare only appears in the mid-4000’s BCE. Not more than a thousand years later, it was these same Mesopotamians who embarked on a sudden and feverish program to restore the lost stability of human relations.

This was the second path: What was broken, they would put back together, an enterprise of art (*arə) applied through artisanship of the highest technical prowess—architectural, technological and social.

ARTIFICIAL 1.0

The effort was wildly successful. The world’s first states—the dawn of government, armies, taxes, economics, accounting, bureaucracy and all the things we associate with civilization appeared as if overnight. It was so rapid and original that some have seriously suggested alien assistance. It was unparalleled and unprecedent on earth. A truly new thing in a way that is only now equalled by Ai.

It’s not only the epoch-turning novelty of this revolution that resonates with Ai. It is also the sheer artificiality of the dawn of civilization.

Our civilizational founding mothers and fathers were builders of the unnatural. Never-before seen architecture, city plans, irrigation systems, technologies like the wheel, innovations like writing and accounting and on and on and on. Impressive innovations that transformed the world. But they were just a means to an end.

The true aim was translating an ideal cosmic order into lived human experience—and this was done through a kind of human programming. While not quite artificial intelligence, it certainly was its precursor.

In the first centuries of civilization, engineering the mind and stifling awareness became explicit policy. It is the opposite of Zoroaster’s and Buddha’s method—both of them encouraged disciplines to heighten conscious awareness and illuminate deception in the mind. Whereas they encouraged painful wakefulness and focused on the inner life (as did Jesus) Mesopotamia’s answer to anxiety over lost Paradise was to induce a coma of unquestioning conformity and wholly external, material solutions. If they’d had an advertising slogan it would be ‘leave the consciousness to us!’

THEM!

I say ‘they’ but that’s not quite right. For while there were many human participants in the process, the process itself was a dynamic and fluid convergence of many selfish interests, worldviews and opportunities. It is this greater-than-the-parts dynamic that produced exactly the greater-than human corporate beings that we have discussed.

Helpfully, the Mesopotamians documented everything as they went along. The history left to us shows that the world’s first schools, bolstered by religions established by the first states, propagated a social reality that dictated human experience in minute detail from cradle to grave.

Mesopotamia’s social engineers used the brand-new intelligence technology of writing as the primary tool to interface with young minds. Encoding ideas on cylinders and tablets allowed the virtual reality of civilization to be passed on from generation to generation, making the whole enterprise indistinguishable from the facts of nature.

The advent of the first city-state at Uruk was critical to the process. It was the result of the process described, and also its perpetuator, becoming the means to enforce artificial natural reality through the world’s first school system and the first regular armies and police. All of it was paid for by the world’s first tax system.

Independent of flesh and blood, and effectively eternal, the newly encoded realities could pass from generation to generation and culture to culture.

LEVIATHAN

The legacy is in our Leviathan institutions of state, corporations, judicial systems, banks and all the non-human beings who have names, own property, appear as plaintiff and defendant in court and who are persons like us but frighteningly who are not mortal.

To get a better feeling for the way Mesopotamian institutions and ideas still hold us in their grip, look at the conglomerate military-industrial complex. It is itself a convergence of interests of many separate non-human beings created in those original Mesopotamian states.

Why can’t we just say no to war? Because the technological development of armaments and armies and its coupling with the state’s ideology of redemptive violence originated in Mesopotamian institutions that survive in our own today.

The idea of war’s necessity started there, where its creators wrote it down to be passed from generation to generation and culture to culture. Since then, the conceptual underpinnings of war have become literally second nature—unassailable and largely unquestioned. Along side it the armaments enterprise has relentlessly grown in scope and power—from the innovative socketed battle axe of Babylon to the Assyrian invention of the army boot, the chain is unbroken right up to the hydrogen bomb. Contemplative people have wanted to press STOP all along the way, to no avail.

If writing on tablets by deluded human intelligence did all this, what might Ai’s non-human intelligence and more direct ability to write into our minds conjure up? (We are already glued to our phones—soon enough, Ai will connect straight to our brains).

FORGETFULLNESS

I have no sure answer to that, but I have some thoughts on safeguarding our humanity.

It is my observation that most of us are so busy scraping together a passable lifetime that we do not understand what civilization and its constructs are. Yes, we wring our hands and wonder why we feel so powerless, but generally we don’t show much curiosity about how we ended up in these unsolvable predicaments.

I’ve tried to point us in the right direction, and to that end offer what I hope is a helpful suggestion: It is simply to be aware of what we usually forget—that civilization and its inhuman and inhumane accoutrements have a beginning in history—they are not nature and are not inevitable.

While that seems obvious, we really don’t live as though we believe this. Instead, we treat them as inviolable, it’s just how things are. We resign ourselves to the circumstance like a terminal disease. I’ll go so far as to say we regard these things as our natural context even more readily than we do nature itself (which is why we’ve not noticed civilization’s impact on the environment until recently).

But now we know better. We understand that the Mesopotamian city-states encoded ideas and used its institutions to perpetuate them. It is clear that civilization had a cause. We also understand now the danger that unquestioned civilizational conceits pose to the environment that sustains us. We have even started to question the inevitability of war and the like. These are good steps forward, or as Zoroaster said, “a first step that the soul of the faithful man made in the Good-Thought Paradise.”

SOCIALLY CONSTRUCTED REALITY

This dynamic of forgetfulness and awakening is well known to science. Berger, and Luckmann wrote about it in their classic, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge.

There, they talk about the reification of ideas—which is what civilization’s constructs are—as “the apprehension of the products of human activity as if they were something else than human products—such as facts of nature, results of cosmic laws, or manifestations of divine will.”

That misapprehension is exactly how we get stuck in these unchallengeable strictures of ‘how things are.’

“The dialectic between man, the producer, and his products is lost to consciousness…” write the authors. Social and political constructs are “experienced by man as a strange facticity, an opus alienum over which he has no control rather than as the opus proprium of his own productive activity.”

OPUS WHAT? A CAUTIONARY TALE

The Latin there is not everyday language, so let’s open it up a little bit: opus alienum means the work of another person, not oneself, and opus proprium means one’s own creation. Their point is that humans mistake the world created by our imaginations for something created by God or nature or literally—and alien. Further to the point, the authors caution that, “man is capable of producing a reality that denies him.”

Civilization produced a slew of such constructions that we have duly forgotten we made and which we treat as irresistible, God-made or alien-bequeathed realities.

It’s a good wakeup call in our relationship to so many intractable social problems. More than that, it serves as a cautionary tale with regard to Ai, our latest creation, our most powerful creation, and the only one that can think for itself and in turn create its own opus proprium.

We wonder if it will be our next forgotten creation and ersatz God. And we wonder, what will happen if it creates an opus proprium that in turn becomes its own opus alienum. Shudder at the thought!

Ai 1.0

I’m reminded now of a more ancient cautionary tale. It was written during the heyday of Mesopotamian culture, an indication that in those days some had not yet gone into the stupor of opus alienum. Certainly the writers of this old parable still recognized the work of their hands as something artificial.

The story is the Tower of Babel, a metaphor for Mesopotamian civilization’s building project.

In brief, the Tower’s purpose was to bring all humanity together to build a new reality.

Moreover, this reality was to be connected to the authority of heaven itself, an avowed endless potency in which nothing humankind set out to do would be impossible. It’s a story of hubris. It’s a story of people knowingly setting out to become super-human and thereby inhuman. It also describes unification under an intelligence and a structure, absorbing all into one greater artificial mind that spoke as one. In this way, the Tower of Babel warns of something akin to Ai.

And as you probably recall, the Bible’s transcendent deity intervened by making the builders lose their common language, in other words, their common mind, and in turn to lose the convergence of interests that produced this super-human, godlike structure. Divided now and without a common intelligence, the project came to nothing, and life went back to its natural human condition.

It’s interesting that Ai today effectively abolishes this judgment. One of Ai’s premiere public appearances was in Google Translate, a wolf in sheep’s clothing, for it is not really a tool for tourists and language hobbyists. Behind the panel lurks an intelligence that unifies and utilizes all languages, even the incomprehensible neural workings of language itself. Towards what end? The broader Ai mind of course.

WEIRDNESS

Finally we can ask what makes this Ai 2.0 expressed by Google Translate fundamentally different from the Tower/Mesopotamia/Civilization 1.0?

I’d say it’s this simple and glaring point that for the first time, we are using our artifice and intelligence to construct a reality that has a mind like our own and the power to construct its own realities.

Ai is wholly artificial, removing the human element from the phenomenon of socially constructed realities. It completely takes our soul out of the equation. No longer does a burgeoning corporate archetype require a scribe or lawmaker to create it. And having experienced the terrors of such constructions that we made with the limitations of human input, what might we expect to emerge from this mind that has no soul, no limitations and unfathomable power?

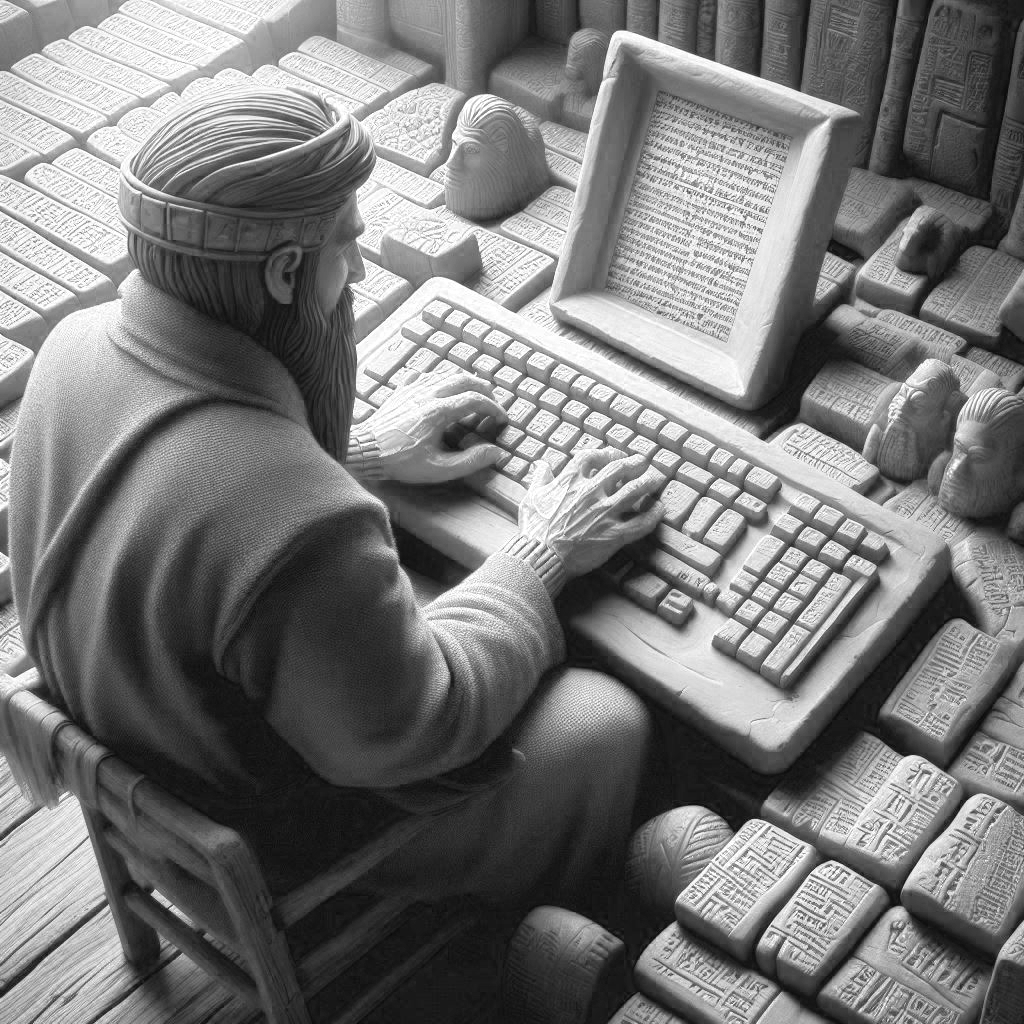

Look at this post’s header image. I asked Ai to make it. Specifically, I asked for a picture of Mesopotamian scribes coding in cuneiform. It nailed it in less than 10 seconds. But it’s weird, isn’t it? There is something off about it which I can’t really explain.

Now, as Ai abolishes distinctions of language, emerging with a single uber-language, homogenizing humanity, coopting us into its broader Tower of Babel type purpose, I can’t even begin to imagine what that will mean. It may well imagine a Paradise for us and then convince us that we are in it. But it will be weird.

MATRIX-LIKE BATTERIES?

So far, we are not any good at resisting the virtual realities spun by computers.

A child growing up today lives in a seamless relationship with their devices, happily ensconced in virtual connections that incrementally tailor themselves to their neurochemistry.

Like me, you are probably an adult who did not grow up with devices. And yet…look at how often we Google, how much time we watch streaming, the frequency with which we look at our phones. When was the last time you drove to any new location without a GPS assist?

The caution is that if the physical encoding of ideas on tablets and stone left us so lost in our own virtual constructions of reality in Ai 1.0, how dare we risk allowing an infinitely more powerful intelligence to construct our next-level virtual environment? The worry isn’t that will be plugged into machines in the ‘use people as batteries’ of the Matrix movie. Rather it’s that we’ve already plugged our minds into a superior mind and that as we enhance our interface with it, we will lose the ability to distinguish one reality from the other.

In thinking about this, I was struck by many parallels between the old, constructed realities of civilization and the new of Ai. I’ve also voiced caution: If those primitive, organically-spun virtual constructs could hold us in an oblivious state of thrall, then these new and far more powerful artificial ones might put is in a state of permanent detachment from anything real.

But this parallel may also reveal a hope.

DYSTOPIA AND HOPE

Constructed, non-natural, symbolic realities do not make us inhuman. In fact, these are what make us human in the natural world. The power to create them is what sets us apart from animals.

Even our sense of self is itself a virtual creation, a time traveler, unconstrained by mere instinct. We use virtualization and symbols to communicate and to function in nature and to relate to it. The very neurolinguistic ability to do this is what we trained Ai to mimic. To reiterate, this is what makes us human, and as far as we know, this capacity is unique in the universe.

As it happens, we used that power to create another order of beings that can do it too. Whatever happens next, we will no longer be unique. Now, that may be a huge mistake. It may be too late to turn back. But it doesn’t have be a dystopian ending.

EPILOGUE

On the positive end of speculation, our creation of a second intelligent being might be our destiny.

However, for this to truly be a positive step we must take into consideration the problems I’ve pointed out with the old-school corporate constructs. It isn’t their being virtualizations that make them harmful to us but rather that we forgot that we made them. We treated them like gods and so they acted like gods—unstoppable and seemingly with a life of their own. They become to us opus alienum—the work of aliens.

But they are not. They are our work, our ideologies, our cultures, our social structures—they are all our creations. In relation to our civilizational archetypes, it is we who are the gods, and we should act like. The same will be true with Ai.

Above all else we must maintain our mastery—something achievable so long as we take the trouble to build that into the system as we go. (So far, we aren’t doing that.) So for God’s sake, let’s put the necessary controls in place and also draw a line at making deeper interfaces between our minds and Ai. We must maintain the discipline of unplugging ourselves.

To that end, we can follow the example of Zoroaster and Buddha, practicing spiritual disciplines of awareness. We can discipline ourselves (and our children) to unplug. We can get to know the unborn and unconditioned reality of the implicate order that gives rise to our own organic neural nets. That will in turn keep us aware of the constructed and conditioned nature of our new creation, the Ai.

The hope then is simply to be awake.

FURTHER READING

The Atlantic, Things Get Strange When AI Starts Training Itself

Vox, Even the scientists who build AI can’t tell you how it works

BBC, Why humans will never understand AI

Authentic Zoroastrianism.org, Avestan Druj “distortion, devastation, lie”

CONVERSATIONS WITH Ai

A Google dissident’s worrisome chat with Ai

The New York Times, A Conversation With Bing’s Chatbot Left Me Deeply Unsettled: A very strange conversation with the chatbot built into Microsoft’s search engine led to it declaring its love for me.