Artificial Intelligence. That was the topic. I ‘d collected notes and was sitting down to explore them when a decidedly non-artificial intelligence grabbed my attention: It was none other than Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and here’s what he led me to think about:

Your kingdom come. Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.

RATIONS

It doesn’t matter your religion or your lack of one, hearing this and the rest of The Lord’s Prayer is a provocation. It makes us imagine its fulfilment. It reveals our hearts. What does heaven look like for me? Am I supposed to bring it to earth? How do I feel when I say father? What is the evil from which I need deliverance? Is a daily ration of bread all that heaven has to offer?

And much more. This isn’t just a prayer—it’s a crucible—it interrogates us and tutors us and tests us.

Now, let me say at the outset, that I believe Jesus lived and breathed and taught these words. But that’s not so important. Much like Buddha, Jesus is a message and a vision that exceeds the scope of whatever human life he lived.

And as we will see, this is very much to the point of the prayer. It exceeds the confines of our temporal journey.

Personally, that’s what decades of grappling with it have taught me. This prayer is not for my vision of heaven, or my will to be done. It isn’t for my economic or political philosophy to be fulfilled. And no, it certainly is not a prayer for tomorrow’s bread or finances (it really is only for today’s ration).

Put in positive terms, it is a prayer for something sublimely beyond my grasp, an unaddressable domain that is not yet of the earth. It is about the transcendent and it is about faith.

In that way, The Lord’s Prayer has a practical application. It can serve as political hygiene, washing off the temptations of big ideas. Used devotionally, it can even be an effective talisman against political hubris. God knows we need that.

THE FIRST PRAYER

Curiously, despite its fame as The Lord’s Prayer, this supplication is not original to Jesus.

It is very, very old, coming from a common understanding that the world isn’t the way it should be. So, in some fashion, these intercessions have been on our lips for at least as long as we have been writing prayers down.

Beyond that general idea, we can also say that neither the form nor wording of the Jesus prayer were novel. It was and remains a common prayer in Judaism, and it is prayed by Jews to this day nearly verbatim.

Consequently, for the typical crowd following a would-be messiah in the first century, praying to Father God for his kingdom to come was neither an innovation nor surprising.

Indeed, Roman historian Tacitus explained exactly what your kingdom come meant to many such people, writing that, “the majority firmly believed that their ancient priestly writings contained the prophecy that this was the very time when the East should grow strong and that men starting from Judea should possess the world.”

What makes Jesus’ prayer unique then? It isn’t his words, but rather his intentions, which he declared to be not of this world. That’s a sharp disagreement with the Jewish patriots described by Tacitus.

S0, given that the crowds following Jesus were full of people expecting to possess the world (or at least their patch of it), why did Jesus teach this common and politically attuned prayer? I think it was deliberate irony, an affronting challenge to the status quo. From his lips, the familiar words entered the consciousness as a conceptual wire brush, scouring away centuries of conditioning and exposing the vulgar motivations of his listeners. Many hated him for it.

A KINGDOM COME

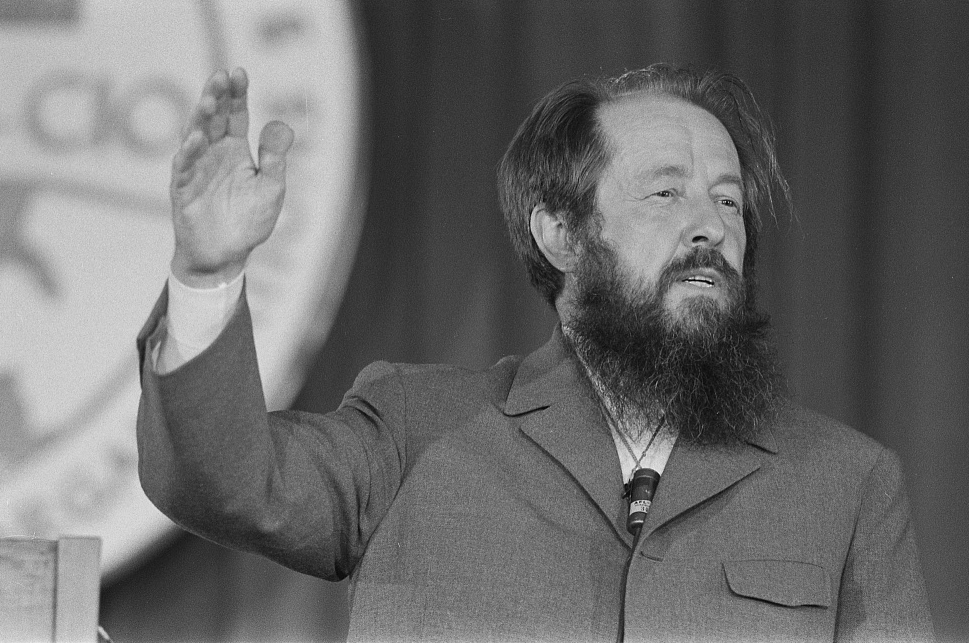

Enter Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Over the past few weeks, as my eldest son and I re-read The Gulag Archipelago, we couldn’t help but think about the desire—indeed about the prayer—for heaven on earth.

That’s because Solzhenitsyn’s book is about life in the Soviet Union, history’s most completely realized vision of Marxism. And Marxism is, if it is anything at all, an eschatology. It is about the advent of heaven on earth and like the Judean zeolots described by Tacitus, it is about possessing it. Remember, Marxist theory consists of clearly delineated and inevitable dispensations of history, which in any other framework, we would call prophecy. And we should call it that, as Marxism is a belief system that makes eschatological promises.

Of its predestined dispensations, the Soviet enterprise claimed the penultimate slot with an explicit mandate of restoring humanity to its eternal bliss.

But does it stretch the point to suggest Russia’s revolutionary clamor was a prayer? I don’t think so. We’ve only to reflect on the final stage of Marxist prophecy to understand this. Characterized as the end of history, it was to be an endless dispensation, a new society without money, without the need for government, with no class divisions, no competing states, and no wars—it is, in every way, a restoration of Paradise.

And it was, in this sense, a fulfilment of the ancient prayer. Remember, millions believed in these prophecies. Millions pled for their realization. Moreover, people longed for it, died for it and killed for it.

Call it an innermost supplication, ardent hope, devout purpose or whatever—when a person is willing to overthrow everything on the expectation of ending history and of introducing a new heaven-like age, it is at the very least, a prayer.

SIMULACRUM

But to whom then did these supplicants pray and whose will and kingdom were these?

Whoever it was, this god was cruel. The heavenly dream was fine (often called The Workers’ Paradise), but once come to earth it became a hell, a place of imprisonment, torture, and ideological subjugation (relentlessly and elegantly portrayed through Solzhenitsyn’s testimony).

Of course, the dream itself was not original. It is straight from the Bible and Zoroastrianism, and appears in dozens of apocalyptic writings from antiquity. Marxism took that and refashioned it into a godless vision, what the founder called scientific socialism. It is thus a perversely materialistic heaven that mimics (or does it mock?) the heavenly kingdom petitioned by Jesus.

In this then, we see who the Marxist God is. It is a humanity reduced to the material realm, devoid of anything transcendent, and effectively taking the place of the Divine. It is precisely the condition of Adam fallen in the Garden of Eden, only now at last full-grown and mature in the 20th century.

THE INTERIM

I’ll look at that again momentarily. First, what of the eons (or perhaps only millennia) between Adam and Marx? To reflect on that, consider the difference between the simulacrum and the original revelation that it mimics.

Most essentially, the original vision of God’s kingdom was indeed transcendent of the material world.

This was the key awakening of the Axial Age, affirmed by the Hebrew prophets and Zoroastrians of the Near East. All in all, the vision was for something beyond the veil of the gross and temporal material realm. Stone and wooden idols fell to the axe and the hammer as the prophets revealed that the Divine could not be reduced to anything describable or locatable. Further afield, Buddhism’s assessment of reality is also unambiguous on this point affirming that reality is not reducible to the material.

We can even say that the original vision frankly accepted that life in the material phase was ultimately a temporary and painful trial that served a greater purpose. In no sense was there ever a plan to “fix it.”

Jesus was of that ilk. We know that because he talked a lot about heaven, economics, and politics. His words convey a clear understanding of what the kingdom meant to him.

For example, in the words that immediately precede this prayer, we hear many of the kingdom’s characteristics. Poverty of spirit, mercifulness, forgiveness, non-violence, and self-effacing spirituality are some hallmarks mentioned there. He also speaks of self-denial and servanthood. What he says about economic concerns was, in a nutshell, that we shouldn’t have them.

BAD POLITICS

Astonishing to us today, rather than pledging to abolish poverty, Jesus sanctifies the condition.

He would make a horrible politician today. Who would vote for a platform of universal poverty, self-denial and mandatory life-long service?

Most crucially, we have Jesus’ explicit, and to his peer group, wholly unexpected statement that the kingdom of heaven is not of this world. It shocked his disciples as much as it did his enemies. When Peter challenged him to fight for his kingdom in the political realm, Jesus said that Peter was setting his mind “on the things of man” “not on the things of God.” (John 18:36, Matt. 16:23) In the same breath, Jesus called Peter Satan. That says a lot—for Peter’s call to action echoes, as we shall see, the temptation of Adam in the Garden of Eden.

TRICKS OF THE TRADE

Sadly, such satanic obsessions became the norm for Christians some three hundred years later.

The catalyst was the Roman Emperor’s adoption of Christianity and ensuing co-opting of the faith. He and his immediate successors set about formally dogmatizing, controlling, and enforcing Christian thought, fusing it with the state to form a frame in which to pour God’s Kingdom as a concrete object. It was to be completely earthbound, culminating in an expected series of last events, and then a physical lowering of New Jerusalem to Earth.

Such a material and political outcome presaged Marxism to a tee. (Except that the Christian empire preserved the illusion of fealty to Jesus while Marxism’s illusion was that it was in no way tainted with the ignorance of religion—different tricks for different times).

In short order, Islam’s early rulers adopted the same template. We should remember that Islam emerged in a Byzantine environment. It was a variation on Judeo-Christian scriptures—complete with the centrality of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount and the full roster of prophets and biblical figures from Adam to Moses, to David, and finally, to Jesus, who, according to the Qur’an, is the Messiah and the Word of God.

TAKING OFF THE MASK

In this way, the Byzantine Empire and statist Islam are just two of the many post-Jesus attempts to invoke God’s authority in defiance of the original revelations. In the West, these pseudo-heavenly kingdoms posed as Christian, tapping into people’s sense of spirituality while in pursuit of the “things of man.” Thus, the Byzantine model prevailed across the centuries, progressively dominating more and more of the world.

By the late nineteenth century, however, the pretense was wearing thin.

Already, the United States had tried to disestablish religion. Earth was Earth, Heaven was Heaven and here on Earth. This was an opportunity for real prudence, but it did not last. To the contrary, American Christians maintained (despite the Founders’ guardrails) a rather severe ‘convert the heathen and hunker down until the Apocalypse’ millenarianism that mixed up American expansion with the will of God. In Europe, God and King remained as one.

But this would not suit growing modern sensibilities. As respect for secularism and science steadily increased, the justification of having God on one’s side became less convincing.

The problem, however, was that those old millenarian political dreams did not go away. That’s where Marxism proves exemplary. It claimed to be scientific while employing the same heaven-on-earth rhetoric and absolute authority as its predecessors. That millions bought this thinly veiled counterfeit testifies to the incredible need we have for heaven.

Marxism was not alone performing this sleight of hand. In America, the new format came through the Social Gospel, which led directly to modern-day secular progressive globalism. At the center of this transition we find the very devout “God ordained that I should be the next president” Woodrow Wilson. It was scientific and modern enough to fit the new age, while keeping God on the shelf to be cited as needed.

RECIPE FOR RUTHLESSNESS

We won’t say more about progressivism or globalism here. For more, you might review The Paradise Paradox chapters about the development of millenarianism in the 20th century.

For our present discussion, Marxism sufficiently exemplifies things common to all secular eschatologies: Firstly, modern political movements are increasingly winner-take-all, total, dogmatic, binding and missionary. In other words, they are religions and fiercely sectarian.

And secondly, they are doctrinally materialistic, (matter describes the universe and no other view is serious or ‘real’).

Together, those two ingredients are a recipe for ruthlessness.

How so? It’s simply that when human life is reckoned to have no value beyond its material being, it will be worth less than any ideology (like Marxism or Progressivism or Globalism) that claims to possess eternal qualities of truth.

The ideology is spiritual and eternal. A human without the image of God is nothing but gross matter, temporary and disposable.

The Soviet situation exemplifies both elements. It is evidenced in the cruelty Solzhenitsyn describes in which the religion of the state tormented humans precisely because they were less valuable (and less real) than its ideal. Make no mistake: despite disavowing God, the Soviet experiment was religious apocalypticism at its blistering hottest—human life became a burnt offering to the necessity of hastening Communism’s End of History.

If this meant the torment of millions, so what? These deviants did not believe the right things! They did not say the right things! They had no vision! They were still thinking in old, regressive patterns! They stood in the way of The People!

And The People (an abstract analog for God, not an expression of humanity) would see its will done on Earth. Dissenters were not The People. They had to be converted, suppressed, or removed from circulation.

SOLZHENITSYN ON SHAKESPEARE

Solzhenitsyn ably describes this viciousness in terms that should chill us who live in a time of maximalist, all-or-nothing political ideals.

To help us understand the danger better, let’s consider one of the book’s most quoted passages. The author introduces it with a reference to Shakespeare’s great villains, whom he finds anemic compared with the priests of today’s secular religions:

“The trouble lies in the way these classic evildoers…recognize themselves as evildoers…they know their souls are black…they stopped short at a dozen corpses.” But what caused this self-judgment, why couldn’t they overcome it?

Solzhenitsyn says it is, “Because they had no ideology!”

“Ideology—that is what gives evildoing its long-sought justification and gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination. That is the social theory which helps to make his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and others’ eyes….Thanks to ideology, the twentieth century was fated to experience evildoing on a scale calculated in the millions.”

GODLIKENESS

Solzhenitsyn prefaced this with the key revelation: “To do evil a human being must first of all believe that what he’s doing is good.”

We know how that works. In former empires, oppressors acted in the name of God, meaning anything they did, no matter how inhumane, was for a greater good. Modern secular ideologies substitute God with The People (in the USA it is always for the monolithic American people that our candidates act) or even History itself (or Freedom, Democracy, Equality and on and on).

I’m going to call the root of this impulse Godlikeness. This isn’t being like God, or being godly. This is an act of counterfeiting God.

In more conventional terms, it is humanism, which seems a benign expression, but it does not mean human, it does not mean humanity. It is an -ism, a belief system. What is its doctrine? That human value comes solely from itself.

As humanism is materialistic, there is nothing transcendent of the human experience (which, to my Buddhist friends, is not necessarily ‘outside’ or ‘above’; it can be within us, transcending deeper than our ego and material being). And without transcendence, humanism is completely self-reflective, a narcissistic limitation producing an ethos that is desperately selfish, for there is nothing else for which to live.

For that reason, humanism relies on itself for salvation. This may sound odd, but millions believe in humanistic salvation. This is the idea that science and correct politics will find a solution to life’s problems; together they will extend life, cure all disease and solve the causes of inequality. The Godlike is its own savior and its salvation is purely material.

THE ARCHETYPE

To explore this further, let’s take up a theme from The Paradise Paradox. Readers of Genesis will recognize Godlikeness as the signature temptation faced in the Garden of Eden. In fact, this enticement veritably drips from the serpent’s forked tongue: “But the serpent said…your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God.”

Now, I’m not hung up on literalism. There may have been an Adam in a garden. But I don’t think it matter. Adam means human in the original language. This story was always anthropological, a study of the human species.

What’s important is that there is a global memory of a before and after preserved here. Held in some form by cultures the world over, the loss-of-paradise narrative recalls a crucial transition in human development. I worked this over thoroughly in the book, so I won’t repeat that effort here except to reiterate this: Adam’s story preserves an ancient awareness that something changed in the human experience.

Specifically, we remember a breakpoint in human consciousness. The before is an experience of heaven integrated with life on earth. The after is an experience of earth bereft of heaven.

When we pray for the Kingdom to come, we pray for the before to be restored.

And that’s just as true if we are praying only to ourselves.

CAN’T I BE GODLY?

Before moving on I should answer what some are asking. If Godlikeness is the fall of humanity, dare we aspire to godliness?

Emphatically yes. If post-fall Adam personifies a satanically inspired counterfeit God, what is Jesus but his redemption—a restoration of Adam, who was created not as God, but in God’s image. Jesus as the Second Adam reveals the original human condition as he embraces transcendence and disavows materialism.

But he is also God incarnate, revealing the nature of God, and in that revelation allowing us to be reconciled with the Divine, restored to the original relationship.

To be Godlike is a delusion of autonomy and control of nature. To be godly is to genuinely be like God, which, as we see in Jesus, means to be more essentially human.

Remember, in their essential humanity Adam and Eve were already like God. Emphatically, they already bore the image of God, “in the likeness of God…created them male and female, and blessed them and called them Mankind in the day they were created.” (Gen. 5:1-2)

As usual in Genesis, the authors play on the words. Created in the likeness of God. Then the serpent tempts them to be like God. We see a dissatisfaction then, not only with their human estate but with who God is. We could write a book on that subject. For now, I suggest this: to be godly is to be more fully human and to be fully human is already to bear God’s likeness. Jesus as God incarnate (and not only Jesus) reveals who God is and what God’s values are (for one thing, God is a servant; for another God is not fundamentally material). Jesus as a human (and not only Jesus) shows what the image of God in humanity is.

FROM ADAM TO MARX

To sum up and connect a few dots:

There is a before, when Adam had communion with a divine presence, a state of transpersonal awareness that was without shaming and without feeling ashamed. (Gen. 2:25)

There is an after, when humanity is cut off from this awareness, feeling naked, alone, and lost (“where are you, Adam?”).

The consequences of Godlikeness follow quickly. Toil and anxiety, enmity and shame, blame and murder; they occur one after the other. Then there is the immediate appearance of the first governments and armies—simulations of heaven all—and all built upon this new Godlike knowledge, an illicitly gained mastery of self-referential Good and Evil, the very substance of ideology.

How this might have happened in anthropological history is the subject of the early chapters of our book. There really were transformations of human consciousness that led to the outcomes remembered in ancient mythologies like Genesis.

Remarkably, those effects continue to gain momentum today. For although reductive materialism was the first-order effect of the Genesis crisis, for most of human history we regarded this as a curse, longing for reconciliation with the transcendent. It is only in the last few centuries that we embraced the curse and confessed it as an inviolable creed: Matter is all that is real.

And yet, consider this: the before had no politics, no hierarchy, no conflict, no economic commodification, no class stratification, no inequality and no want.

This is the very model for the Communist stage of Marxist eschatology, demonstrating that even those who deny God and disparage the Bible live gripped and motivated by what is remembered there.

MEANING

And materialism is deepening and hardening, with Artificial General Intelligence, human hybridization with machines—including staring at our phones—biomedical engineering and more, we desperately try to replace the missing divine with material simulations. Buyer beware.

Let us harken again to Solzhenitsyn:

“If humanism were right in declaring that man is born to be happy, he would not be born to die. Since his body is doomed to die, his task on earth evidently must be of a more spiritual nature. It cannot the unrestrained enjoyment of everyday life…. It cannot be the search for the best ways to obtain material goods…. It has to be…that one’s life journey may become an experience of moral growth, so that one may leave life a better human being than one started it.”

When he made this speech at Harvard in 1978, many found it disconcerting. The honored escapee from Soviet oppression was expected to criticize the Communist Bloc, not deplore the West’s loss of spiritual values. How dare he?! The USSR was bad; the USA was good!

Instead, he says the West suffers from the same faulty premise that condemned the Soviets—materialism.

A HARD LESSON

Elsewhere he doubled down on his premise, recalling that as a youngster people often explained their horrifying predicament as a crisis of faith:

“I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: ‘Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.’ Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years working on the history of our Revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous Revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: ‘Men have forgotten God; that’s why all this has happened.'”

He goes on to share this hard lesson, gained through years of imprisonment and torment:

“Our life consists not in the pursuit of material success but in the quest for worthy spiritual growth. Our entire earthly existence is but a transitional stage in the movement toward something higher, and we must not stumble and fall, nor must we linger fruitlessly on one rung of the ladder.”

I like his rungs of the ladder. He is saying don’t get hung up on false securities like money or obsession with your physical condition. Our material state is a passage. Getting distracted by attempts to preserve it is a waste of life.

EMBARRASED

Transcendence? Something higher? A life lived mainly for what’s beyond it? This is embarrassing to we materialists. Where’s the science?

Many prominent voices ridicule us for thinking there is any meaning beyond matter. “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.” That’s Richard Dawkins writing in, A River Out of Eden, (1995). (However, he couldn’t resist a call back to Genesis in his title!)

Such voices shame us who have seen otherwise. Reluctant to discredit ourselves, we blush and brim with caveats when we speak of what we know. Faith is OK, but not as reality, only as ritual, (or a hobby, in the words of Evelyn Waugh.)

Our global culture constantly re-enforces this and, it seems to me, beguiles us. We work for material gain, with its implicit promise of a scientific breakthrough that might cure our mortality, or we sit in a state of hypnotized entertainment, unable to face the abyss that is the truth of technology’s dead-end street.

However, if we were a little more awake and a little better read, we might be more skeptical of materialism and less embarrassed.

Take heart from physics. There we find a frank admission of what exists beyond our senses and a warning about the independence and objectivity of observation and measurement.

INTELLIGENCE

Even mathematicians can give us support. How about Kurt Gödel? It is fair to say that, along with his friend Albert Einstein, he re-laid the foundations of science.

As a logician, he ranks among the most persuasive and brilliant in all of history.

In the discipline of mathematics, he was a Mozart, leaving his envious peers with jaws dropped and the field transformed in his wake.

Later, Gödel’s work on Einstein’s field equations succeeded in improving and magnifying the work of one of the greatest minds in human history—an illustration of Kurt’s powerful insight and clarity of logic.

He also absolutely believed in eternal life. “If the world is rationally constructed and has meaning, then there must be such a thing,” he wrote.

He read the Bible too. One passage that he bookmarked in his pocket Latin New Testament (bracketed and pointed out with an arrow no less) embarrasses many Christians who, if they mention it at all, go to great pains to explain it away:

“The body is sown in corruption; it is raised in incorruption. It is sown in dishonor; it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness; it is raised in power. It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body… Now this I say, brethren, that flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God; nor does corruption inherit incorruption.… For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality….’O Death, where is your sting? O Hades, where is your victory?'”

Kurt wasn’t embarrassed, you don’t need to be either.

POINT NO. 10

Blind faith? No, says Gödel, “I am convinced of this independently of any theology.” In other words, he came to this position through reason.

In particular, it was math, logic, and science that led him. His theorems (the groundbreaking incompleteness theorems first) bolstered his belief that there is life beyond material life. He even explicitly declared that reductive materialism was a delusion. Lest there be any doubt, he helpfully left a written list behind entitled, What I Believe. Point No. 10 was: “Materialism is false.”

I cannot stress too much that Gödel based these beliefs on his powerful grasp of logic, an understanding of physics capable of improving Einstein, and on mathematics that were transformative.

He is far from alone. Consider too Arno Allan Penzias. The Nobel Prize winner in physics, co-discoverer of cosmic microwave background radiation, widely considered the best scientific evidence for the Big Bang, said this: “My argument is that the best data we have are exactly what I would have predicted, had I had nothing to go on but the five books of Moses, the Psalms, the Bible as a whole.”

INCONCLUSIONS

In wrapping this up, I don’t want to leave the impression that belief equals certainty. That’s always been the downfall. To abstract, reify, or objectify God or heaven is to miss transcendence all together. The warning and moral of the Genesis story is exactly that we cannot know as God knows.

Instead, answers to questions like what is God? must be agnostic. Otherwise, our mistaken certainty creates material simulacra like Marxism’s Paradise or the Islamic State’s caliphate, or the Crusader’s kingdom in Jerusalem (or Netanyahu’s for that matter). Certainty of what is not measurable is delusional hubris.

True faith must answer I don’t know because it transcends the material realm of sensory certainty. Simply, there is that which is beyond language, measurement, and testing. Likewise, we ought not try to specify what the afterlife is exactly. After can be nonlinear, in the sense of behind or beyond. Transcendence is not framed by time such that it is sequenced on a timeline. It can be alongside our experience of time, or it can contain it, or be an unseen layer, a higher dimension. It can be transcendent of sure knowledge but still completely plausible and not contradicted by what we observe in known physics. It can be real and still unknowable in the scientific sense.

But the answer can also be I know God. Adam walked with God, communed with God. I know God too. I know God like I know anyone else. We have a relationship, I enjoy God’s presence, I recognize God’s voice. This is unmediated knowledge, non-defining. It isn’t what, it is who.

MUSIC

We know music like this too: There is no single note that is the music and not even a sequence of notes that define it—the music exists in the recognition of it, what Henri Bergson called la durée. This is music as it transcends frozen points in time. The minutes, seconds, individual notes, and the pitch and timbre of music occur one sound at a time, temporal and material.

I can certainly have knowledge of those elements by notation and as measured by frequency. But this is not the experience or recognition of music. I can play each sound individually for you and point them out on a page as I go, but you’ll not know the music from that either. Music exists in the flow, in the overlapping relationship of the sounds in a way that is beyond our neurological registration of the sounds themselves. We really don’t understand how that happens. It is transcendent of the material and demonstrably transcendent of the physiology.

Knowing God is like that. The kingdom of heaven is like that. It is beyond definition, beyond capture, beyond simulation. All we can do is pray for it come, recognize it amongst us, and rejoice that it is not doomed to be possessed and reduced to the material realm.

SELAH

סֶֽלָה

Next quarter (or sooner) I will try to come to terms with AI. It is the ultimate simulacrum, God in a box. Is it materialism’s deathblow to what remains of original human nature? What universe will it create? I don’t think I want to bear its image.

FURTHER READING:

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Solzhenitsyn Aleksandr. 1975. The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation. London: Collins & Harvill, 173-174

A World Split Apart, Commencement Address, Harvard University, June 8, 1978https://www.solzhenitsyncenter.org/a-world-split-apart

Templeton Prize, Acceptance Address by Mr. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, MAY 10, 1983

The Lord’s Prayer

The Jewish Origins of the Lord’s Prayer, Rabbi Leo Abrami.

My Personal Test for Ideology Poisoning

How I test to see if my ideas threaten my humanity. I ask myself: What do I feel about the leader of the other group? Not my rational evaluation, but how do I feel about them. Fury? Anger?

So Cain was very angry, and his face fell. The Lord said to Cain, “Why are you angry, and why has your face fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin is crouching at the door. Its desire is contrary to you, but you must rule over it.”

Kurt Gödel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gödel%27s_incompleteness_theorems

https://aeon.co/essays/kurt-godel-his-mother-and-the-argument-for-life-after-death

https://plato.stanford.edu/Archives/spr2020/entries/goedel/index.html

Wang Hao. 1996. A Logical Journey: From Gödel to Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 107-108

Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder (excerpt from the book and the 1981 script adaptation).

“The view implicit in my education was that the basic narrative of Christianity had long been exposed as a myth… religion was a hobby which some people professed and others did not; at the best it was slightly ornamental, at the worst it was the province of ‘complexes’ and ‘inhibitions’ – catchwords of the decade – and of the intolerance, hypocrisy, and sheer stupidity attributed to it for centuries.

No one had ever suggested to me that these quaint observances expressed a coherent philosophical system…Nor, had they done so, would I have been much interested.

But I later recognised some such spirit in myself. Later, too, I have come to accept claims which, then in 1923, I never troubled to examine, and to accept the supernatural as the real.”