Religion isn’t the cause of violence in the Gaza, nor is diplomacy the fix.

The true root of violence is the cult of victimhood.

PART ONE: WHOSE SIDE ARE YOU ON?

We were driving through Israel’s Negev desert. It was October 8 and now we were about 15 miles from the slaughter and kidnappings of the previous day. Our destination was a hotel in Galilee, where many of the survivors would be sheltered, and where we would wait in uncertainty.

NOT THE FIRST TIME

I had time to think, and so I thought a lot about barbarity of this kind, and how often I had crossed its path, and how likely it is to happen again.

Given the present circumstances and fears of Hezbollah rockets from Lebanon, my mind naturally drifted back to 1982, when I was living on Israel’s northern border. There was a war on then too, with rumbling tanks and nighttime flares and daily news of casualties.

I could understand the practical reason for this war. The farm I lived on had been subject to PLO Katyusha rocket attacks. Operation Peace for Galilee aimed to eliminate that threat. Consequently, I thought little more about it. Wars happen. That’s just the way things are. War was a problem solver.

Or at least I thought that until news came of atrocities committed by Israel’s allies. The perpetrators were Phalangist Christians. Much like Hamas 40 years later, they butchered babies, raped and humiliated women, and slaughtered civilians. Although Israelis were not directly involved, the militia had signalled its intentions, and the assault took place under Israeli auspices.

I was shocked and it made question the status quo of violence for the first time. Why would Christians do these things? Why did Israel allow it? And why, really, had the PLO wrought terror on civilians in the first place? It was enough to make me realize that Middle East conflicts weren’t merely caused by grievances that could be negotiated away at a conference table. There was a metaphysical motivation here—something larger in meaning than ordinary material concerns. This seemed to point to religion as the culprit, but I doubted that it was as simple as that.

So, if not exactly politics and not exactly religion, then what? I began to think about it in terms of some common temptation that believers faced and succumbed to, something to do with their expectations of life. It was, I thought, related to the original temptation of Adam and Eve, but I could not quite yet grasp what the connection might be.

PATTERN OF INHUMANITY

As it turns out, I’d have many opportunities to examine the problem, and as I became more involved with events in the Middle East, I’d get a much closer view. Of these, one of the most notable was Saddam Hussein’s 1989 chemical attack against Kurds in northern Iraq. I debriefed victims of that attempted genocide, hearing stories of terrifying sounds in the sky, clouds of smoke (it was poisonous gas) and people dropping literally like flies where they stood, left laying seemingly frozen in time.

I scarcely comprehended the magnitude of what I heard and found the crayon tableaus that the children drew especially disturbing—they scrawled them obsessively, trying to make sense of a world unraveling around them.

Here too was a metaphysical cause, this time related to Arab Baathism. It was a religion of ethnicity, with its own promise of perfected society and a personality cult that imagined Saddam as a scion of the ancient Babylonian Empire.

VIOLENCE EVERYWHERE AND MUTED HOPE

Since then, these gruesome scenarios have become routine and expected in our work. We’ve stayed busy: helping torture victims heal, caring for orphans of war and terror and for displaced families, and less than a decade ago, assisting victims of the bloodthirsty Islamic State in northern Syria—a community of refugees that I continue to work with today.

It’s easy to ask, “what’s wrong with those people in the Middle East?” But incomprehensible, soul-destroying violence is strewn across history and occurs everywhere, from school shootings in the USA to ethnic cleansing in Myanmar and from Ashurbanipal’s ruthless march through the ancient Near East, to terror and mass murder by the Mongols, and on to Stalin’s regime, the Holocaust and 9/11.

We must remember too that the West always has a hand in modern Middle East conflicts. Just because our populations are usually shielded from the fallout doesn’t mean we aren’t a part of the insanity—we certainly are. Moreover, to escape the scourge entirely is an exceedingly rare and privileged position.

And it’s a deluding one: the next outbreak will come, and eventually near to us or our children or grandchildren. It will also be worse than what we’ve seen before as the democratization and automation of weapons of mass destruction brings the unimaginable nearer each day.

A MUTED HOPE

Bleak assessment that this is, I’d like to offer some muted hope. Muted because I can’t honestly say, “don’t worry, be happy.” All I can do is point out a supporting pillar of systematic violence in the hope that helps us to pull it down.

You see, it isn’t human nature for us to do these things. We know that because the violence we speak of is socially constructed, organized, calculated, and has an origin in relatively recent history.

HEAVEN ON EARTH – OXYMORON?

In various forms this is about a vision of heaven on earth and to do with a reality that many cannot accept, namely, that heaven is heaven, earth is earth, and that life here in the flesh is best lived in humble recognition of its limitations. This is the fundamental temptation that Adam and Even speak to and the temptation that drags religions into violence. Adam and Eve fail to the temptation to be like god ruling their own heaven on earth—simple human life in the Garden of Eden wasn’t enough.

It’s a disastrous ambition and when heaven on earth is imagined as an enforceable social project, all hell breaks loose. Frequently there is a frankly religious identity involved in these operations (the Crusades for one, recent jihads and so on). But any heaven-on-earth ideology is essentially a religion in the throes of falling to temptation. Even in recent history, idealist utopian visions have motivated non-religious death campaigns on the ideological right (Nazism) and the left (Stalinism). I’m sure many more examples of these kind spring to mind.

Some examples may not be so obvious, however—they are too close to us and too ordinary. Consider for example the horrific suffering in Iraq since 2003 and everything that sprang from it, including the Islamic State and myriad Iran-backed militias. It is the fruit of neoconservative nation-building ideology. And as we now know conclusively, this exercise had nothing to do with a threat from Saddam Hussein—it was driven by the idea that America had a mandate to reshape the world as a better place, in its own idealized image.

As we can see, when convinced of the power to bring heaven to earth, anything or anyone standing in the way is liable to be subjected to violence or left in its grip as an unintended consequence of imposing the fantasy.

PROS AND CONS

Tracing that theme in history and mythology is very much the subject of my book, and I hope you’ll read it. For now, however, I want to focus on a very present and current issue through which violence sustains itself.

Put simply it is the oppressive and urgent demand that we take a side.

Through protests in the streets, tweets, and slogans, the current Mideast crisis asks that we denounce or defend one side or the other.

These calls do not press for detailed assessments and are not about justice regarding specific instances. Instead, they insist that we endorse or denounce entire nations, identifying one and then the other as either a pure victim or a demonic butcher. So which are you—pro-Palestine or pro-Israel?

Evangelists for either side present arguments to secure our conversion. For example, the demand to be “pro-Palestine” will highlight Israel’s remorseless guilt and Palestine’s role as innocent victim. Although few will outright defend Hamas atrocities, many who make this argument will discount them, insinuating that Israelis brought it on themselves. They oppressed and occupied Palestine. Didn’t they have it coming?

Or to flip the argument, there is Israel’s unremitting campaign to eradicate Hamas at the cost of innocent Palestinian lives within Gaza. Didn’t the Gazans bring that on themselves by electing and supporting terrorists who refused peace with Israel—and then celebrating their horrific attack on Israeli noncombatants?

It can easily become a trial of public opinion as to whose status as victim justifies the most violence in return.

In this tribunal we are expected to issue a black or white judgment. There might be no harm in that except that our expressed stand in favor of one or against the other influences our decision-makers and enflames and encourages proponents of violence on the ground. Our opinions have real consequences for Israelis, Palestinians, Jews, Muslims, and Christian Arabs.

CAN I BE PRO-BOTH?

To illustrate, I’ll use my own situation. For many of my friends, any posture but an avowed anti-Israel one appears hostile to Palestinians. In response, I’ve been obliged to point out that this is an antithetical fallacy. The truth is, I can be pro-Israel and pro-Palestine.

To that end, I’ve sometimes had to bring unwanted and discomfiting complexity into the discussion. For example, as part of their argument, some friends said that Hamas attacked Israelis living on occupied Arab land. This fit their “the Israelis brought it on themselves” narrative.

That’s a bad argument to begin with, even if the premise were true. It isn’t. The Israelis that Hamas attacked lived firmly within Israel’s internationally sanctioned borders. Strikingly, the community that I’m most familiar with, one that bore the brunt of the brutal Hamas assault, is populated by liberals and advocates for peace. These decidedly were not “settlers.”

I’ve also had to challenge the notion that Hamas equates with Palestinian. It’s more complicated than that. Hamas is different from the PLO and there is a difference between Gaza and the West Bank (some of my friends did not understand that). Understanding that the roots of various Palestinian organizations are starkly divergent is important. Their relationships are complex and sometimes violent, and their aims do not always align. Knowing this helps keep us from simplistic pro and con tribalism. Just as it is possible to be antagonistic toward any given American political movement and still love America—one can denounce Hamas and love Palestine. I am against Hamas and its stated goals. I support Palestinians and Palestine.

In the same way, I can speak against the idea of prophecy-driven Israeli settlements on the West Bank and support and love Israel. To denounce their ambitions does not equate with being “anti-Israel” and indeed a huge number of Israelis stand against the settler movement too.

Really, the way I see it, Jewish settler dreams of End Times theocracy mirror exactly the theocratic vision of Hamas. How does that translate into sloganeering pro or anti Israel or Palestine? It doesn’t. Sloganeering of that kind is juvenile, callow, and dangerous.

WHO STARTED THE FIRE?

Unfortunately, getting into the complexities beyond this can quickly become pointless. Accusations of aggression and claims of original victimhood ricochet back and forth. There is always the ‘but before that, they did this’ argument. The aim is to reach some essential starting point where the true and blameless first victim can claim the title and be justified in further bloodshed. If they are blameless victims, their violence is to be excused.

There is a profoundly dark and profane bloodlust in this cycle—unredeemed, nasty, and inhuman. We can do better.

VICTIMHOOD

A starting point is to reflect on this compulsion to claim original victimhood. Remember, it is the pretext for communal violence—a special status that makes subsequent violence in the cycle OK.

In this counterfeit faith of victimhood, violence is a means to an end. Brutality becomes a rite of redemption, a final spasm of violence to end all violence. On the other side awaits a better world.

We associate this more easily with fanatical religions and extremist politics, yet in practice, the phenomenon is mainstream. How does an ethos like that thrive in a modern world of lightweight pop culture, in a world of YouTube and TikTok? Quite well, it seems. If anything, popular culture propagates this process with viral tales ever in search of a victim to celebrate and a villain for the #HERO to punish.

That’s not surprising to me. American entertainment provided a template that I grew up with. It’s the cowboy gunslinger who shoots the bad guy, saves the girl, brings peace to the town and the end credits roll, a genuine religious mythology if ever there was one.

Unbelievable, right? On the face of it, we know violence is not redemptive and that there is no convenient “THE END” graphic to halt the cycle. And yet we very quickly conform to this mythology. Tell us a moving good versus evil story and off we ride, endorsing and funding killing. All it takes is the unsupported say-so of politicians who assure us of the final victory and peace to follow. As a whole, we are gullible and gormless acolytes of this doctrine of violence.

So it is a religious problem after all, but a religion all its own, practiced by confused monotheists of every type and by materialist ideologues alike.

And the issues that diplomats focus on? Mundane land and resource disputes or legal equities? These do not hold the solutions because they are not really the problem. The true problem is in this cultic cycle. No solution will hold without addressing it.

PART TWO: MAGIC IS NOT WHAT YOU THINK IT IS

LEARN WAR NO MORE

I can see how all three Abrahamic traditions can deal with the above-mentioned false religion. I can see how non-theistic Buddhism can handle it too. But as a Christian, I’ve been reflecting on it through Jesus.

Now, before you turn away, hear me out. I’m not looking at Jesus as a Sunday school cartoon. Instead, I’m talking about Jesus as a statement of collective consciousness, a way of grappling with the very problem of violence.

That’s a big assertion, and to understand how it might be true, we should consider the role Jesus plays more broadly in history. To being with, we know his context is the Roman Empire. But it’s bigger than that. The Romans were part of a larger stream of history and consciousness. Their system came from Mesopotamia. Indeed all our systems of government and ideas of statecraft and warfare originate there.

Very importantly, Mesopotamia patented the structures of government, dominance, inequality, exploitation, and systematic warfare that remain with us today. Even accepting that some of Mesopotamia’s inventions were good for us, (interest rates and taxes?) a great deal of what it brought was excruciating. It’s for good reason that the region’s great dynastic empires (like Babylon) became bywords for human affliction. The title was well-earned.

Note too, that in apocalyptic writing around the time of Jesus, Babylon was code for Rome—the people of the day understood the origin of their oppression very well indeed. And they had understood it for centuries. The Jewish prophets and other Axial Age thinkers (including Buddha) had questioned the legitimacy of Mesopotamia’s status quo ethos for hundreds of years.

The vision that emerged was for everlasting peace, true freedom, and welfare for all people. In biblical literature, which synthesized and critiqued Mesopotamian culture, this hope is explicit. Salvation was an alternative world order where people beat their swords into ploughshares and learned war no more. (Isaiah 2:4)

HUMAN SACRIFICE

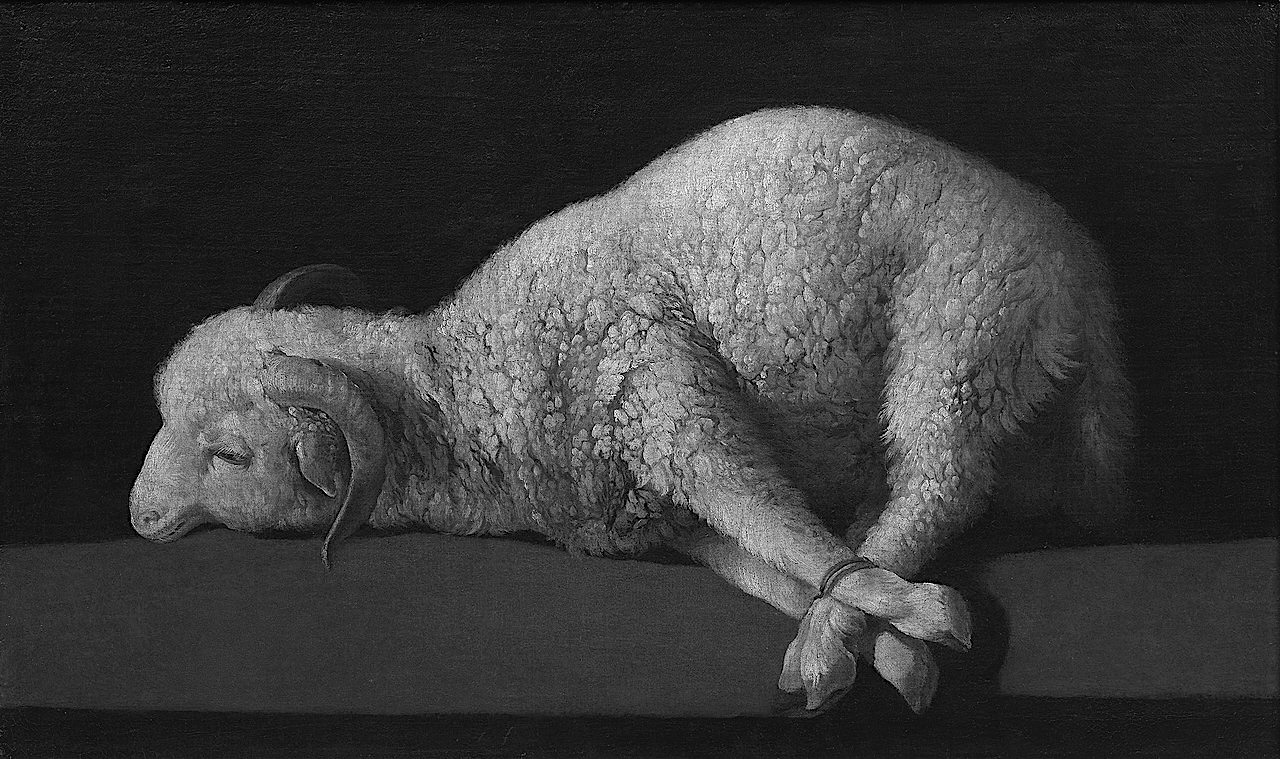

It’s a big subject, but our concern now is related to the cycle of victim and violence. That leads us to consider Jesus as a the universal and single victim, the sacrificial Lamb of God.

This idea references a Mesopotamian archetype, namely the practice of ritual sacrifice. It was a kind of state-sponsored violence that boiled down all the other violence and domination into a single symbolic act. The Mesopotamian city states usually offered animals, foodstuff and wealth to keep in good relations with heaven. But they sacrificed humans too, even children, for purposes of big consequence—things regarded as existential or essential.

Hebrew culture had it too. Jerusalem’s temple revolved around sacrificial offerings. But there was an odd take on the practice: woven into the fundamental narrative of Israel’s beginnings we read a criticism, expressed dramatically in the biography of Abraham—father of Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

Who he is and where he is from are as much a part of the lesson as what he does. Scripture goes out of its way to introduce Abraham as a Mesopotamian, a notable citizen of one of its greatest cities. As such, he certainly was no stranger to human sacrifice. In fact, the Bible records that as he was about to sacrifice his own son, God instructed him to offer up a ram instead.

ENDING THE STATUS QUO

Early Christians, Jews and Muslims understood what this meant. They recalled that Abraham’s people practiced child sacrifice. Moreover, the Bible itself records that sacrificing children was ubiquitous in and around Jerusalem until very late in ancient Israel’s history.

These accounts are not remembered as “our enemies are so awful that they kill children” but rather as “this is what we used to do before we came to our senses.”

And that’s really what Abraham’s story is about—he represents humanity having a cultural epiphany, an awakening. In this way, he stands for humanity at large, showing that we don’t have to do things the way we’ve always done them.

A LONG LESSON STILL TO BE LEARNED

He showed the way, but human sacrifice did not stop. To this day we still sacrifice people. We are just less honest in our rituals and kill far more people than the ancients did.

Here’s what I mean. Even in their time, Mesopotamia’s ordinary rituals of state militarism killed far more people than religious sacrifice did. Foreign military campaigns consumed the lives of the empire’s youth and the lives of their enemies. The rationale was to establish a better world by making the most true and just system the dominant one. Sound familiar? Of course, everyone thinks theirs is the best system—that’s key to the fallacy.

So, why is this horrific civilizational system so durable? It has to do with the nature of socially constructed reality. Made up ideas like war and cowboys become like laws of physics over time. “It’s just how things are.”

Accepted over generations, we forget that we made these things up, and they enslave us.

GOD ON THE ALTAR

Here again, Abraham, as the consummate Mesopotamian, speaks powerfully to the possibility of realizing that we don’t have to go along with “just how things are.” Abraham realizes that sacrificing his child to guarantee the promise of a better world is not required after all. The God he thought he was sacrificing too provides a substitute. It is a conceptual breakthrough, a shattering of the constructed reality.

As Lamb of God, Jesus takes it a step further. Instead of offering a substitute animal, Jesus represents the divine order offering itself as the substitute. That’s important because in the Mesopotamian context, Divinity is the source and authorizer of the system and its violence. Thus, the authority relied upon by the progenitors of civilization to construct our social reality itself renounces the construct. That’s the beauty of it.

But how does it work? What does it do if it is only symbolic?

NO HOCUS-POCUS

There is no hocus-pocus here, no alchemy or wizardry. To the contrary, the magic spell was spun by civilization’s status quo. Magicians subvert our observations of reality. Sleight of hand and misdirection lead us to believe convincing illusions. That’s what the authors of civilization did.

The necessity of violence and other inviolable structures of society are illusions, magic tricks. Jesus and Abraham exist to unmask those illusions, to reveal the trickery. It’s as simple as that.

In short, as constructed realities come from our words, ideas and symbols (or mythologies), they can be deconstructed in the same way, through narrative and symbols. The well-timed and well-placed Jesus message can replace the Mesopotamian paradigm. It can replace the American gunslinger myth too.

So the mechanism is substitution in a literal sense. It conceptually replaces the possibility of victimhood with a one and only all eclipsing victim, and importantly, a completely innocent one. And since our social realities are entirely conceptual, it is as real as any other.

The symbolic substitute victim is blameless because there can be no presumed “he had it coming.”

But neither can there be a perpetrator to blame, and so the substitution is voluntary.

A blameless and voluntary sacrifice is thus a firebreak in the cycle of victim and retribution.

PROGRAMMING

The relevance of this to modern life astonishes me. I said there is no hocus-pocus, no magic involved. Instead, the Jesus message exposes the preceding frame of reference. “The trick works like this,” says Jesus, and we see through it, no longer enchanted. In a sense, he and many other Axial Age thinkers before him, wrote software to reprogram us. Just install the Jesus paradigm and let it do its work.

Some of that is explicitly instructional—directly overwriting our linguistic programming. That fits well with Isaiah’s original vision of peace, when he writes that they “will learn war no more.” So true. These awful ‘realities’ are learned. We can learn something different.

Importantly, Jesus flatly instructs us that there can be no heaven on earth—not a Jewish one, not a Muslim one, not a Marxist one, not even an American one.

His core message thus denies the fundamental motivation for ideological violence. With Jesus, the Kingdom of Heaven is not “of this world,” for if it were,” “my servants would fight….”

Because heaven can’t be here, there is no cause for our holy wars (even progressive secular ones).

JESUS AND LIBERATING PALESTINE

Helpfully, the politics of Jesus’ age parallel the modern Holy Land. Palestine was occupied. Roman soldiers prowled the streets. Rebels, militias, and those who by any definition were terrorists—they all claimed to fight against the occupation on behalf of Rome’s victims. The death toll reached some two million by the end of it and included mass executions and ethnic cleansing.

Appearing just before the outbreak of all-out war, Jesus appears at a moment of high expectation for a militant messianic redemption. And there were numerous would-be Messiahs staking their claims, right up to the bitter end. The Messiah’s job was clear to most: he’d save Israel from its infidel occupiers through a divine war to end all wars. (I discuss this at length in my book).

But Jesus rejects the premise. We see it in practical terms: one side scolds him for not being pro-Israel and the other condemns him for being anti-Roman.

As we saw, his kingdom-not-of-this-world speaks to the possibility of a truly different kind of social reality. It speaks to today’s Holy Land just as aptly as it did in the first century.

RELAVENCE AND REVOLUTION

Indeed, the Jesus story addresses much of what we are dealing with now: violence, politics, victimhood, religious bigotry, Palestine, Jerusalem and more. And the message speaks not just to the Middle East, but to all the powers that dominate the global stage today.

Just consider the characteristics of modern states. Our nations and governments continue to function in alignment with the Mesopotamian model. But at the same time, all of them have a Judeo-Christian connection that preserves the dream of repealing the status quo.

Our hopes and dreams of progress are end of history ideas. We want to get past the Mesopotamian age and find the age of peace and welfare for all. Even China is beholden to a philosophy derived from Marxism, a utopian dream of history’s end rooted in the Middle East’s monotheistic religions.

But here’s the rub: together we face the temptation that Jewish zealots faced in the first century. We want to get past the status quo, but we can’t seem to let go of its violent processes and behaviors.

It’s the trap every revolution to date trips over, the delusion of a Paradise on earth achieved through a final bloody conflict. We look to cowboys and armed messiahs to win the day.

The Jesus message and others like it can simply change our minds if we are open to it. Perhaps that’s what our rallies should be about instead of fanning the flames of pro and anti politics.

CAN PEACE BE VIOLENT?

Is violence ever justified, perhaps a non-ideological, non-messianic, completely utilitarian and dispassionate violence?

Maybe so, but we easily kid ourselves. For example, the United States adopts the role of the “world’s policeman” who is on the spot where needed to contain a greater violence by means of a lesser one. It’s judicial violence.

Another example is judicial punishment through the penal system, up to and including executions. Isn’t that OK? Much depends on whether we regard this violence as redemptive or salvific. Do we feel empowered and vindicated when someone “gets their due”? Do we imagine it is making the world a better place, or are we aware that any need for such measures is a failure—that it’s a sign of the world becoming a worse place?

Surely there are times when violence imposes itself on us, requiring a violent response to contain it—in that case it’s a good thing, right? How about World War Two?

It’s a good example. It shows how violence can impose itself on peace. But it also shows that peace cannot impose itself on violence (because to do so is an act of violence). The suffering, the loss of community and family and faith, and the fact that WWII left the human race in a far more precarious position, means only one thing: it was a colossal failure of humanity, not something to gloat about. There was no salvation to be had within the existing civilizational paradigm.

ABSALOM MY SON

King David might help us with this. His son Absalom was the leader of an insurgent rebellion. Justice caught up with him and he was killed. A messenger brought the good news to the King: The threat to national security is over! The Crown can rest easy!

David’s response shows why the LORD said this imperfect king was a man after his own heart. He did not gloat in victory but recognized the execution as a failure: “The king was deeply moved and went up to the chamber over the gate and wept. And as he went, he said, ‘O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!'”

As with King David, the correct response to the unavoidable execution of violence is that we would rather die in place of the aggressor if this would end the cycle. And in this, again we see Jesus.

HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE?

In the days after October 7, as I reviewed the apocalypses that I’d encountered over the years, I also thought about how optimistic we were in those decades. We generally expected things to improve.

Now I can see there is a danger in such positivity. Optimism can be very much like the millenarian’s expectation of imminent heaven on earth.

Oftentimes optimism is just like that, it is a kind of religion. This kind of optimism comes with a coercive ideology. Consider nation-building in Iraq or the freedom of the Arab Spring. There we see that optimism has no qualms about toting a gun. Or at a minimum, it is quick to pass a new law to stifle the ignorant opposition.

It can be just as bad, however, when it is not so pushy. Indeed, optimism more often presents itself as passive. In that guise it is a see-no-evil stance of wishful thinking that accepts—even pays the bill—for violence afflicting others. “It’s not likely to happen here,” the thinking goes. Then there is a 9/11, or a Pearl Harbor, or a school shooting. We wake up with a look of surprise and say, “Nobody saw that coming!”

This will have huge consequences for the world. We’ve never used the nuclear weapons stockpiled across the globe; it hasn’t happened yet, so it will never happen. It’s a gambler’s optimism. In truth, every year that passes is another spin of the roulette wheel. Each passing day is a day closer to nuclear war. We can’t beat the odds.

PESSIMISM AS A VIRTUE

I think we’d be better off as pessimists. Let’s put wishful thinking aside. Expect that if weapons exist, they will be used. Adopt a careful approach to politics, recognizing that it is a tightwire act such that any hasty or forceful move might set in motion the means to our own end.

Prudence will serve us better than idealism. And perhaps out of an awakening of prudence, and an awareness of the myth of redemptive violence, we might even bring ourselves to defang those nukes. Or at least to think more carefully before we chose a side.

RELATED READING:

THE EXTREME AMBITIONS OF WEST BANK SETTLERS – THE NEW YORKER