Traveling across Mesopotamia and the Holy Land a few months back, I took along William Dalrymple’s fine travelogue, From the Holy Mountain. It was meant to be a colorful diversion along the lines of the author’s earlier Middle East offering, In Xanadu, in which he traced the steps of Marco Polo. Xanadu was great fun, and as I planned to cover much of the same ground mapped out in Holy Mountain, I hoped for more of the same.

But this reading proved unnerving. It was an amnesiac’s recovery of a lost moment, a deja vu of episodes that were familiar and yet not quite my own. Unlike deja vu, however, once awakened, these memories lingered. At night I dreamt them, and I suspected that if Mr. Dalrymple could read my diary, he would experience the same confused anamnesis.

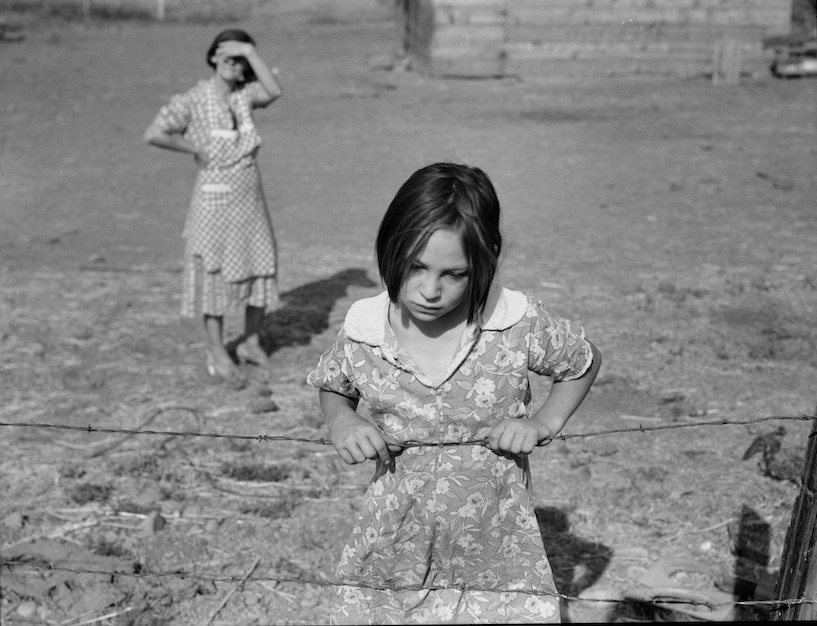

Snapshot.

This was not madness, however. All the details of time and place were firm and quite real. I could pinpoint everything. It was the 1990s. The scene was that troubled corner of the map which thrusts Turkey, Iraq and Syria unhappily together. Our recollections blended easily together because, as it turns out, Mr. Dalrymple and I traveled there at the same time some thirty years ago, each of us experiencing unforgettable, even traumatizing events that now, in their similarity, cannot easily be disentangled from one another.

To be specific, we visited exactly the same places, moved on the same roads and lodged in the same monasteries and villages. We were in and out of the same taxis, (if not the very ones, others just like them), while even the same military police arrested us, (again if not exactly the same, ones indistinguishable from them). So when Dalrymple wrote about certain roads, shadows of plainclothes agents and terrified drivers whose lives he jeopardized, I knew just what he meant.

The main difference is that I was there much longer. Dalrymple’s brief chronicle represents just another shift in my workaday life, a vivid but thin slice of routine that began with my arrival to work with Afghan refugees and the disfranchised Kurds in the mid-1980s. My exposure was so long that it can be blurry and unfocused. That’s what was so powerful, I think, about Dalrymple’s account. The short window of his exposure captures for us a scene otherwise lost; one by which we can judge our own time, uncovering a wealth of meaning and contemporary relevance.

God’s servants.

Of special interest is Dalrymple’s account detailing his ins and outs along the Syrian frontier of Turkey’s Mardin province. They call this the Tur Abdin, or Mount of God’s Servants. It is the fabled homeland of Syriac Christians.

Clearly in need of a drink, the author writes about his adventures among the Servants after the fact, having reached the safety of T.E. Lawrence’s old Aleppo haunt, the Baron Hotel. There, Dalrymple sips his whisky “under an endearingly ludicrous picture of two top-hatted English coachmen” and calls to mind the horror that was Turkey: arrests, threats, “roadblocks and minefields,” and the cautionary specter of a body hanging from a tree.

Through his prose, we feel every minute of what was a tense and difficult several days, culminating in an anxious scramble to reach the Syrian border at ancient Nisibis. Once there, “the Turkish border guards rifled through my rucksack, snagging suspiciously at the mosquito repellant,” Dalrymple recalls. What worried him most, however, were his notebooks. If they confiscated those, his work would be lost and his friends would reap the consequences of their secrets being exposed. “Finally, at two minutes to three, in the sweltering heat of a Mesopotamian summer afternoon, I crossed the no-man’s land”. His notebooks survived unmolested. He was now in Syria.

Garden of Eden.

What next? Syria was notorious, famous for torturing prisoners as much as anything else. But all we feel from Mr. Dalrymple is relief. With a deep inhalation he writes the sentiments of the reprieved: “Immediately the atmosphere changed,” he reports, and then seems to realize that we need an explanation. “Syria may still be a one-party police state, but it is a police state that leaves its citizens alone as long as they keep out of politics; certainly it feels like the Garden of Eden compared to the tension on the other side of the border.”

This safe haven, I don’t need to tell you, is today the most war-torn part of modern Syria. It is filled with armored personnel carriers, burned-out car-skeletons and checkpoints. All the relaxed and happy people that Dalrymple describes in Syria either took up arms or fled to Turkey, their lives decimated. The lucky ones replicated the author’s journey in reverse, crossing into Turkey to experience relief and breathe the fresh air of Eden.

No short cuts.

Does any of that make sense? Turkey was in the 1990s a secular democracy and firm NATO ally. But it was terrifying. On the other hand, Syria was under the thumb of the frightening Assad regime but it was Edenic by comparison. To the enlightened mind this is disconcerting. So too the modern reality, as we consider that the war-torn parts of Syria became a horror only in the wake of liberation from Assad. Meanwhile, Turkey’s status as a place of quiet refuge came about only with the rise of an Assad-like ruler, the authoritarian Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Of course, that’s not the story we want to hear. Our stories are about liberating the oppressed from tyrants. Democracy makes people free. To make sense of it, you will have to take time to travel through these fraught borderlands with us on a journey of understanding. But be warned! There are no short cuts here. The map is complex, and to navigate it requires patience and attention to detail.

First stop: the bad guy.

We can start here with Syria. Few people paid attention to it before the Arab Spring, and when we did begin to take notice, it was because of a thrillingly simple-minded story: Through social media, ordinary Arabs organized themselves against their oppressors! Liberation and Democracy stood waiting in the wings! The White House decreed that President Assad must go! Elections would liberate Egypt too! The Arab Winter of despotism was over, the Spring of Democracy had arrived!

We were to understand that under Assad the country was an unbearable place to live. But this was the same regime (now led by Assad the Second), which had ruled Syria for decades. If it was so bad, how could Dalrymple liken it to the Garden of Eden? And why then, after the country’s north freed itself from Assad during the Arab Spring, did the place become a living hell? Isn’t that all backwards?

If we don’t bother to think it through, we might blame Assad for the post-liberation chaos. Sure, Aleppo’s suffering came by way of ravaging assaults directed by Assad and Putin. But it was as much to do with the city being taken hostage by Islamist freedom-fighters as it was to do with the government’s brutal attempt to regain control. Before the city was “liberated from Assad” it was just fine. Under Assad, Aleppo was very nice indeed. In fact, it was a fine place for a girl to go out uncovered or for a Christian to enjoy a whisky.

Moreover, many parts of northern Syria escaped government assault for years after their freedom was won. They remained firmly controlled by rebels. Why weren’t these places habitable? Why did their residents prefer to move north, into Turkey? It’s hard to blame Assad for that. As I warned, the map is complex….

Across the frontier.

Considering the other side of the fence is just as baffling.

Reports about Turkey today talk a lot about dictatorship, repression of freedoms and persecution. President Erdogan represents the new wave of strongmen marching across the world stage, a kind of Islamist Putin. As Reporters Without Borders states, “The rule of law is a fading memory in the ‘New Turkey’ of paramount presidential authority.” Much of what we hear about is the struggle of Kurds for freedom. How does that add up to becoming a safe haven for Syrians, a great many of them Kurds? Surely Turkey is the same horror show that it was when Dalrymple and I were there thirty years ago. Is Erdogan’s regime really preferable now to the Assad-free lands of northern Syria?

Comparative oppression.

We’ll get to that in a moment. First let’s consider the criteria of oppression.

By now we understand that for those who did not actively oppose the regime, life was decent in pre-war Syria. To be sure, the state was heavy-handed, allowing no criticism. The government imprisoned and tortured thousands. Cronyism and corruption began to affect many places, especially in drought-stricken agricultural regions. (Yes, Climate Change was a factor in Syria and Iraq.) And let there be no doubt, for those caught in the punitive gears of state machinery, life was a misery under Assad.

But this much is true to varying degrees everywhere. While the rules are more or less stringent from place to place, states punish defiance the world over. For comparison, consider the US incarceration rate. It is currently at 758 per 100,000 (the highest in the world). Meanwhile in Syria it was 58 per 100,000 at the peak of Assad’s power in 2004. This means that under Assad, ordinary people were less likely to see the inside of a prison than any given American in the good old USA. And, you might recall, America even sent extraordinarily rendered prisoners to Syria for torture in those days. America outsourced human rights abuses to the dictator whose enemies it later armed to depose him. Complexity.

Among the Kurds.

As for Kurdish citizens of Assad’s Syria, the official policy was disenfranchisement. Indeed, the state flooded the border towns with Arabs to dilute the Kurds’ sense of autonomy. But they could, however, openly express their culture. They could speak and sing Kurdish. They were free to make money, raise a family and own property. In the 1980s and 90s Kurdish political parties maintained operations on Syrian soil. This included Turkey’s banned PKK separatist party. So in comparison, life for Kurds in Syria could be better than it was in Turkey. For politically active Kurds, it was far better. All this despite Syria’s being an Arab republic that confessed an officially Arab identity.

It wasn’t just the Kurds who breathed more freely. Just about everyone in Syria was free to practice their culture as they saw fit. The regime curtailed most political rights, but a Syrian’s cultural and religious freedom was envied by many across the Middle East. An exception was the Muslim Brotherhood, which wished to depose the presidents Assad. The Muslim Brothers remained suppressed and harassed. Complex.

Image: Carlos Latuff [Public domain]

Meanwhile among the democrats.

No such liberties existed during the same period in democratic, dictator-free Turkey. No one could speak Kurdish freely during the 1990s. Turkey’s democratically elected government allowed no legal Kurdish newspapers or broadcasting. There were no Kurdish political parties. Anti-terror police routinely busted citizens for playing Kurdish music cassettes in their cars. Leftists were rounded up by the truckload. Large areas of the country suffered under emergency rules that gave special police units the right to arrest, torture and kill.

My personal experience of those days amounted to drinking tea with families whose members were in prison. Again and again they told me harrowing tales of torture. They hoped my reports would make America put a stop to it, naively thinking that America’s leaders simply didn’t know. But they did already know. What the US Government did instead was to sell Turkey more attack helicopters. These were better suited to penetrating the Kurdish mountains than to fending off Russians, and we knew it.

The Christians of Turkey’s Tur Abdin had it even worse. Their numbers shriveled under more than a century of withering persecution and racism. Between 1890 and 1930 the number of Christians in Turkey dropped from 20 percent to less than 2 percent. By the 1990s, when Dalrymple visited them, the community reached its nadir. On this account, the contrast between Assad’s Syria and democratic Turkey is even starker. Arab and Syriac Christians were completely free to practice and express their faith in Syria, where the muscular state protected them.

Allah not a racist.

Alright, so a Syria free of Assad proved to be worse than his dictatorship and Turkey under a democracy was a miserable place to be. And now Turkey is less free, but apparently a happier place than liberated Syria. Can that be true? Is it true even for the Kurds?

I can answer that definitively as a long-term witness. Compared with recent decades, persecution of the Kurds in Turkey is practically nonexistent. Kurdish music and regional Kurdish-language broadcasting is normal in today’s authoritarian Turkey. Nowadays, Kurds proudly and publicly celebrate their Kurdishness in ways unthinkable in the 1990s. To win an election in Kurdish areas, candidates routinely mount their slogans in Kurdish and appeal to their ethnic bona fides. The same behaviors would land you in jail a few decades ago.

The difference is that in the old days, Turkey’s secular democracy established a nationalist ideal that allowed only for an ethnic Turkish identity. Astonishingly, Turkish nationalism applied itself even more rigorously than the Arab version expressed by the likes of Saddam and Assad. Worse, Turkey’s was a racist ideology largely underwritten by NATO allies.

Today the policy is less secular, less democratic, and less Western, but also less racist. The new identity is Islam, a religion that overarches ethnicity. Allah has no predilection for one race over the other. It is an equality of submission. All must bow to the greater identity of Islam. In that way, Turkey is now more like the Ottoman Empire; it is a place where authoritarianism is linked to one man and his religion. Under Islam, it’s OK to be a Kurd. Complex!

Beyond the headlines.

What about reports that President Erdogan persecutes Kurds? Alas, this too is complicated. Usually his wrath has to do with the atheistic and anarchistic ideology of some Kurds. Specifically, Turkey’s leader opposes the powerful separatist party, the PKK. This is because they run afoul of Erdogan’s interpretation of inclusive Islamic society. It is not, however, about their ethnicity. The Erdogan-led state is equally harsh with non-Kurds who threaten it or otherwise undermine the new era’s edict of state prescribed piety.

Consider too that a solid twenty percent of Kurdish voters still hold their religion very dear. They support Mr. Erdogan and vote for his party. This number would be higher if not for so many families becoming entangled, mafia-style, with the PKK in the 1990s. In any case, out of 297 members of parliament, 50 are Kurds. This means their share in parliament is equal to the percentage of Kurds in the total population. Erdogan brags about the number of Kurds in government. But thirty years ago, if a Kurd happened to be elected, his ethnicity was never mentioned. Indeed, it could not be mentioned.

Kurds in today’s Syria.

Returning to the border crossing, let’s specifically consider the unique situation of Syrian Kurds today. Of all communities in northern Syria, they certainly have the best prospects. To live as a Kurd under the victorious Kurdish militia is about as good as it gets. That doesn’t, however, mean Kurdish families feel safer than the average Kurdish family in Turkey.

How can they? Although the Kurdish militia is one of the winners, it is a recent gain, and it is still a war. Remember, there was a period of years following the Arab Spring ten years ago when the Islamic State decimated entire Kurdish cities. Just five years ago, the Yezidi and Christian inhabitants of those Kurdish areas faced genocide. Even now with the Kurdish victory, life is not safe nor is it quiet and comfortable. The whole areas is militarized, unstable and under constant threat. It is mainly a paradise for partisan combatants.

Not to forget the Arabs.

We can say the same for the liberated Arab parts of the north. Only there, it is even more chaotic. Factionalism pitted one millenarian Islamic militia against the next for the duration of the war. Aleppo wasn’t just destroyed by Russian and government bombardment. Half the city was effectively held hostage by religious fanatics. The game was to use civilians as a canvas upon which to paint a picture of victimization. Militia members waited eagerly with cameras ready to record the latest civilian caught in the crossfire. Ordinary people counted mainly as propaganda fodder.

Now, after many years of pulverizing government assaults, much of the ground in Arab areas is back under Assad’s control. Nothing was gained. The Arabs who remain free of the regime continue to live and die at the whim of religious fanatics. Who but millenarian lunatics can claim Arabs in Syria are better off now than they were in Assad’s heyday?

By contrast, there is no question that under the fiercely watchful eye of President Erdogan’s tightly controlled Turkey, Arab Syrians live more stable, secure and peaceful lives. More than three million Syrian refugees in Turkey vividly illustrate this in a tableaux of human pilgrimage. A majority of them live in the southeast, the part of Turkey that so terrified Mr. Dalrymple in 1990s.

To that point we can add this: Among the refugees are Assyrian Christians, returning to the Tur Abdin in a surprising reversal of a century-long trend. Most surprising of all, an extraordinary number of the pilgrims are Kurds. They would rather live under Mr. Erdogan’s shadow than under the syndicalist Kurdish militia that dominates northeastern Syria.

Don’t complicate our story!

That even Kurds might choose Turkey is one of many details in the picture that few observers have time to appreciate. Another is that ethnicity is not so simple. Many families are mixed: Arabs, Kurds and Turks intermarry. As outsiders, we want Middle Eastern people to play certain roles, to fit our categories. We want it to be easy. We want the black and white and red and blue of ‘the Turks’ and ‘the Kurds’ and ‘the Arabs’. Shades of gray confuse us.

Our gaze is therefore a divisive one. Do we even realize how often we force people into ideological or ethnic camps? Rather than emphasizing what is shared, we tend to separate people into factions that we understand, and then we arm them against each other. We tend to frame every problem in the region in racist or religious terms and white hats versus black hats. It is a childish way of looking at things.

We mean well, of course, but looking honestly at these asylum seekers reveals considerable resistance to the West’s good intentions. Very few of these people care about the ideals that drove the conflict in Syria to begin with. The story that was so important to us is not often the one that’s important to them.

For example, getting rid of Assad was crucial to the evangelists of global democracy, but ordinary Syrians cherished stability for their families far above that lofty dream. Regular people with businesses and families simply don’t care that much about political theory. These ideas were more valued in Washington, where they held no consequences, than in Aleppo, where they could mean the violent death of a son or daughter.

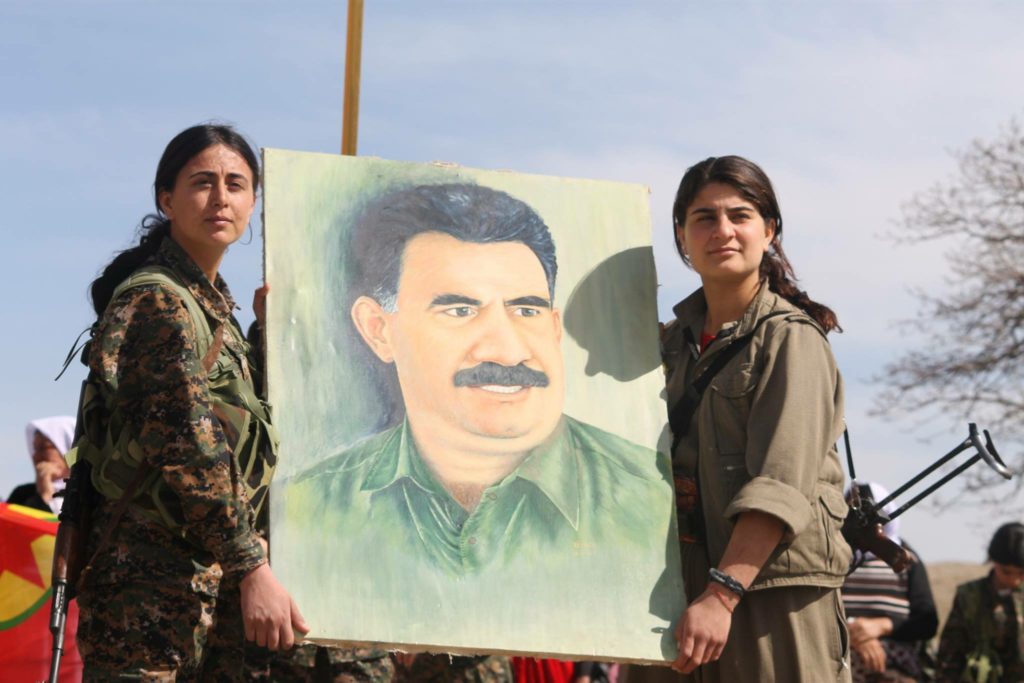

Photo: Mada Media [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

Springtime.

During the Arab Spring, a peculiar kind of liberal Orientalism skewed the story. Orientalism is usually taught as a flaw peculiar to conservatives. The term is shorthand for seeing the Middle East through the distorting lens of Western culture. But liberals also excel at viewing the Middle East through their own ideological filters, and nothing is more illustrative of this than the West’s approach to Syria.

Again and again we impose our own narrative. We even take the appalling position of deciding which Muslims are authentic. For example, Presidents Bush and Obama blithely insisted that Muslims who espouse Islamic dominance—who number in the millions—are not real Muslims. Real Muslims are secular and democratic, obviously. Therefore this is surely what Syria (or Egypt) wants to be. Both presidents seemed to think that given the chance, every Arab everywhere wanted to be just like them.

They could not grasp that the protests across the Arab world in the mid-2000s was about something other than Western ambitions. Certainly the protests were real. There were already demonstrations in Syria during the hard financial times of the early 2000s. Democracy? It’s a nice word, but what if the majority don’t believe in equality? True, ordinary people wanted reform. But reform is not a bloody revolution. Only crazy fanatics, religious and otherwise, wanted improvements at the cost of all-out war.

Evidently some of those crazies lived in Washington. How else did we wind up backing the madmen in Syria? It was they who ended up carrying American-made weapons in what American politicians characterized as a fight for freedom. Our story of Democracy was our fantasy. The men who ended up with guns told different fairy tales about Muslim theocracy or socialist utopia. We did not listen to their stories.

Good guys and bad guys.

At this point, it’s hard for the Syrian refugees I know to see any benign motivation outsiders might have had. Why did we fan these flames, arm those rebels, and provoke the wrath of the regime?

Ask anyone about it and the conversation quickly turns to a discussion of meddling, conspiracies and devious hidden motives. People are fed up with it. Enough with the rebels, the Islamic Caliphate, American Democracy, Kurdish nationalism and the rest of it. They are not just fed up: they never wanted any of it in the first place. Some even rap about it, both in Syria and among the refugees in Turkey. One of the best examples articulates a widespread grasp of something many experts cannot conceive: there are no good guys in this war. That’s a story well worth listening to.

Civic competence.

Comparing Syria and Turkey, it is therefore helpful to consider this very simple metric—how hospitable are these places to human life? By that measure it is obvious that being ruled by a strongman does not preclude happiness for most people. Both places score better on the hospitality test under stern rulers than they do under ‘freedom’.

This brings us back to a jarring fact. In the oppressive 1990s, Turkey’s government was elected and without anything close to a dictator at the helm. Yet, this was among the worst times to be Kurdish there. The cruelty expressed through local governors—mainly against Kurds, Islamists and Communists—was done at the behest of elected officials. Democracy here equalled oppression.

In other words, majoritarian rule can be as despotic as any dictatorship. That’s not news: America’s Founding Fathers fretted over this very thing; they did not romanticize democracy. But we need this reminder; Democracy is a tricky business; it requires a certain level of civic competence from its constituents. Where that does not exist, it might not be the best thing.

So the question before us is not the legitimacy of the Syrian or Turkish government in ideally democratic terms. The question is whether or not the pursuit of ‘freedom from dictatorship’ is worth the price of shattered stability.

Not an easy decision.

Millions of Syrians answered that question with their feet. They fled the chaos of emerging Syrian freedom to the safety of growing Turkish authoritarianism.

During the years when Syria began to shake off its dictator, while Turkey was embracing its leader in ever-more dictatorial poses, approximately 16 percent of Syria’s population fled from Syrian freedom into Turkey’s authoritarian arms. Actually, the percentage is higher if it includes only the areas ‘liberated from Assad’ during the war. The cities producing the fewest refugees were the ones that remained under his control.

Kurds often tell me they were happy in Syria before the Arab Spring but that those days are gone forever. One man articulated for us what’s on many minds. “When the war started everything in our lives changed. Settling in another country was not an easy decision. We had a great life there in Syria, owned a property. But in the end, it is clear now that if we had stayed, our children would no longer be alive.”

Home.

Turkey is now their home. The war lasted a long time. Syrian children are growing up and going to school in Turkish towns and have no desire to leave. To them, home is not some place in Syria about which they have only traumatic memories, if any at all. Where they live now is similar to where they come from, except there is no violence. The population is a mix of Kurds, Arabs and Turks; the culture is more or less the same. On a practical level, it is Syria, only safer.

It is true that the parents sometimes face discrimination. That’s mainly because of economic rivalry and because there are so many refugees. But there is no raging war—Mr. Erdogan won’t allow it—and there has been no serious conflict stemming from resentment of refugees. This, even though some towns took in Syrians in numbers equivalent to the existing local population, effectively doubling their size in just a few years. We might even say that a big piece of Syria itself simply moved a few miles northward.

At the end of the day Turkey remains far more prosperous and materially secure than Syria by any measure. Consequently, it is becoming hard to find anyone apart from militia members who are eager to go back.

Source: Kurdishstruggle [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

“Politika.”

Again, we might assume that of all the Syrian refugees, Kurdish people might be most inclined to go return. Surely they must be tempted to try life under the brave new Kurdish entity in Syria. Indeed, judging by the breathless reports heard in the West, they’d be fools not to join this “utopian experiment”.

Then again, maybe they are not so naive. Once more it may be an example of our story colonizing theirs. While most reporting on the Syrian Kurdish organization romanticizes it, Kurdish refugees have their doubts. At the very least, they tell a more nuanced story.

That’s because the Kurdish utopia has a dark side. In a recent conversation, one of the refugees expressed his concerns in words of exemplary humility. “We Kurds destroyed ISIS, but Kurds have faults too, as far as they continue with weapons. The PYD fights with heart and soul but they have no politika. It’s time they made agreements with other countries on the ground in Syria. Right now they have no basis for building a state.”

What he means by “politika” is non-revolutionary stability. There is no stabilizing policy and no room for organic social relations. Everything is continual revolution and conflict. It is unnatural and abstract. “The Kurds from our region are already in Turkey,” he continued. “For Syrians to be sent back is really dangerous. There is no life there except threats from armed elements. Who will be attacked by whom and for what reason is never clear. Because of that, exposure to danger is constant. For those reasons I don’t want to go back.”

Women’s liberation.

For many, there is also a question mark over whether turning young Kurdish women into militants is really the best thing. They fight as celibate nuns with the picture of their mustached guerrilla leader on their sleeves. Is desexualized guerrillaism really equal to empowerment? I can’t be the judge of that; but neither can I escape feeling that they’ve been married off to the fabled Kurdish leader, brides in a warrior cult.

On this point I’ve spoken with numerous families who say the Kurdish militants coerced them into giving up their children. I know young women who joined the militia at gunpoint. Sometimes they remain sympathetic to the movement in spite of this. Sometimes I do too. There is no denying that it is a symbol of identity and hope for a downtrodden people.

It’s also understandable that considered from the vantage of New York’s unbloodied left-leaning newsrooms, Syria’s Kurdish movement is a thrilling phenomenon. But again, that’s our story. It is liberal Orientalism. For most of the Kurds I know, fighting in a stateless cult-like militia is not what they dream of for their kids.

Aborted freedom.

We mean well. Our aspiration for freedom and welfare is noble. That we want it for others is likewise laudable. Achieving those conditions is not, however, guaranteed by merely overturning a despot. If anything, this widespread Kurdish embrace of strict leaders with mustaches betrays a hunger for authority. This is true whether they color their whiskers Islamist like Erdogan or syndicalist like the PKK’s Ocalan.

Not that a revolt should always be out of the question. Sometimes, when serious efforts to peacefully transition to a more benign system fail, there might be cause for a fight. But that is rare. And if freedom is the goal, it is never going to happen by arming ideologues whose minds are the definition of inflexibility. Gentleness and prudence must discipline any change.

Freedom, we must remember, is a fragile creature; it is dependent on a matrix of strictures and releases. Real freedom craves gentle stability. It must grow organically and be born when its time is right. Woe betide the lunatic who imagines he can open the womb early.

Christendom.

To conclude this meditation, let’s remember where we began. It was with William Dalrymple crossing the border into peaceful northern Syria after many harrowing days in Turkey.

He was there in pursuit of a Byzantine monk from Damascus, a man who traveled the length and breadth of the Christian empire around the time Muhammad was born. (Yes, it was all Christian back then.) Dalrymple’s quest was therefore particularly concerned with the ancient Syriac Christians. How have they fared in liberated Syria?

In brief, Christians are not safe anywhere outside of Assad’s direct protection. This includes the Kurdish region where the Islamic State once ruled Christians without mercy. Of course, compared with the Islamic State, almost anything is better, and on paper, the Christian situation under the Kurdish regime looks great, their rights are secure. However, there are many complaints by Christians about how things work in practice.

Assad is not a perfect host either, but once again he at least represents a stable and safe relationship for Christians. A leading figure in Syria’s Christian community spoke to journalist Flavius Mihaies in 2016, summing up the situation nicely. “Christians find the president Assad a protector…. Until now, the opposition did not present any good things to the rest of the population. We are seeing only Islamic opposition and takfiris against everybody,” he remarked. Takfiris refers to an Islamic practice of designating others as apostates. “We don’t know when we will have real democracy but until then he—Bashar Al-Assad—is the best.”

Ignorance.

When the fighting first began in Syria, it was Christians who first appealed to me for help. They were baffled. Why was the CIA facilitating arms transfers to fanatics? The first news I had came from a personal email: Islamic extremists overran a Christian village. People were beheaded, bodies fed to the dogs.

The reaction I got most commonly back home was that this was certainly propaganda; surely there were not that many extremists among the rebels! That doesn’t fit our story! We should support the Syrian opposition! Dismissed as the ravings of corrupt or unwitting accomplices of Assad, the Christian appeals were mocked and ignored as Islamophobic.

Now that very objection presents itself as naive to the point of foolhardiness. It was, after all, a prescient warning of things to come. It was a glimpse of what was about to happen with the Islamic State, al-Nusra and everything else. But who even remembers? It was eight years ago, after all. We are tired of that story. What’s it got to do with us anyway?

Freedom redux.

Just about everything. More than 6 billion dollars and at least 300,000 direct civilian deaths in the Global War on Terror are all about us. It was our story to begin with. It was a fantasy about Democracy and Globalization. We’ve had everything to do with it.

At the very least, as taxpayers in Western countries with militaries and armaments engaged in those lands, we owe it the people living there to pay more attention to what they are saying and experiencing. We ought to start listening to their story for a change. The very least we can do is pay attention.

In the next post, I want to explore freedom by way of the origin of the war in Syria. This will include a discussion of President Obama’s handling of the situation and the comparable path America followed in Iraq under President Bush. Both ended in woe because of similar romantic, utopian ideals—one pursued by a Republican, the other by a Democrat, they had more in common than many realize.

Related pages:

- My page on Syrian Kurds: Kurdish Politics in Syria: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

- And a brief introduction penned by me on Christians in Syria.

- Bonus page on Arming the Arab Spring: Liberal Orientalism’s Quest for George Washington?

- My comments on the wisdom of revolution, The American Revolution: They Did It, Why Can’t I?

Quran verse: hear what Islam says about itself.

This quote from the Quran often appears as a call to action in Islamist literature: “He it is Who sent His Messenger with guidance and the religion of truth, that He might cause it to prevail over all religions….” The Holy Quran, sūrat l-tawbah (The Repentance).

Unless noted, images copyright the author.

Title image: Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Lange, Dorothea, photographer, LC-USF34- 020397-C [P&P] LOT 304

Image Abdullah Öcalan: Halil Uysal [CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]