There may be some naysayers who doubt that it’s a serious problem for humans (sorry koalas!) but at last global warming is getting the attention it deserves. Everyone is talking about it! The Climate Apocalypse is nigh!

But wait…what is that I hear? Is there a note of optimism sounding in this report of doom? Indeed there is! And that’s the funny thing; it’s as if accepting global warming is an inoculation—one sharp jab of reality protects us from the ravaging effects of the whole. We are even proud of ourselves. “I don’t use plastic bags anymore.” “I drive a hybrid.” “My business buys carbon offsets.” Things are looking up!

Or take for example the case of young Greta Thunberg. My observation is that her message, as damning as it is, evokes a narrative of relief too. Here the thinking goes like this: “At last people are listening!” “Her generation will turn things around.” “She put those Republican deniers in their place!” Much relieved that Greta is on the job, we go to the garage, fire up the car and carry on with habits too deeply ingrained to be revised. It’s an odd optimism, a curious silver lining to the darkening, hot rain clouds that lie on the horizon.

Deep Shit.

This cheerful disposition, however, must withstand the preponderance of contrary evidence from which I’ll call to mind a few points now. Read along even if you know the subject well, because I want to look at the issue afresh in the light of this tendency toward optimism. For those who are put off by a hint of science, I apologize; but our review is only a little bit technical and well worth the five minutes it will take to read.

Let’s begin in 2008, when a group of NASA scientists determined that with CO2 concentrations higher than 350 parts per million (ppm) we will no longer live on a “planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted.”

That’s a sobering judgment, and the science was solid. Their conclusions were based on air bubbles in ice core samples going back 800,000 years. For context, remember that humans first popped their heads above the bushes only 200,000 years ago, so at no point in our sojourn on the planet has CO2 been higher than 350 ppm. Actually the report said the number should be lower than that, but apparently they considered a lesser target unrealistic. This compromise goal (I can only conjecture) was to preserve some optimism about achieving it.

You see, when they wrote this report, CO2 was already around 385 ppm, so the scientists were pressed for time. Urgency leaps off the pages. For example, they wrote this evaluation of the then current CO2 level: “If the present overshoot of this target CO2 is not brief, there is a possibility of seeding irreversible catastrophic effects.” Let me interpret: “the present overshoot” means the 385 ppm level. “If it is not brief” means unless we get off that number really quickly. “Irreversible catastrophic effects” means, well, it means being in planet-wide deep shit. It means CATASTROPHIC EFFECTS.

Black magic.

Since that call to action, our world has been abuzz with we-can-do-it efforts to rise to the challenge. Meeting after meeting agreed to resolutions and limits. As is our global wont, industries sprang up around the issue. Money was to be made. Corporations contrived well-publicized pledges and reconfigured their processes. Most of all, we turned to the black magic of buying carbon offsets.

This too is an exercise in optimism, practiced on an enormous scale so as to let huge corporations off the hook and make consumers feel better. Individuals fall for the gambit when they blithely buy an offset with their airfare and fly on in smug satisfaction. (My airline of choice has an app for that! It calculates that erasing my CO2 liability for an upcoming flight from London to Los Angeles will cost me £14.55.) The whole scheme is nothing less than buying indulgences, and is very nearly literally that. We buy carbon credits to reduce the consequences of our climate guilt—what is it then, if not a new version of medieval men purchasing absolution from the Pope?

Of course, today it is a different kind of transnational catholic body that presides over this voodoo. The world’s multibillion dollar carbon transfers are validated by the United Nations, traded in blocks of 25 tons of emissions—the annual average for a household. You can make some money too. “Nasdaq offers futures and options contracts along with clearing services on key global benchmark products” says the front page of their commodities web portal. “Our product slate includes power, natural gas, crude oil and refined products as well as carbon emissions.” Yes, you read that right, carbon emissions is a commodity these days, just like oil or soybeans and traded on all the world’s major exchanges. Step right up folks! Buy some smoke!

Well, alright, what’s the harm? Nothing overt. Go ahead and deal in carbon credits. But know that it is an insidious practice. We know for a fact that there is no possibility that offsets will mitigate CO2 production enough to make a difference. We’d need an extra planet of trees for this to work. The whole exercise is one of passing and making a buck. Plus, as the planet warms, other CO2 sinks like peat are poised to release their gasses, not soak more up. The priests of climate agree: the UN has stated it is concerned that “offsets also risk giving the dangerous illusion of a ‘fix’ that will allow our billowing emissions to just continue to grow,” calling it “a get out of jail free card.”

Time to call the the COP.

Let’s move on. Here we are eleven years after the benchmark report. Carbon offsets are a scam. Planting new trees is good but it won’t help if the temperatures are already rising. So how are we doing on that score? What’s the temp? To find out, we will turn to the experts, our friends at the United Nations whose job it is to track and predict these things.

If you have any concern for the environment at all, you are probably familiar with the succession of United Nations Climate Change Conferences, usually headlined as COP#, which stands for Convention of Parties, followed by a number representing how many conventions were held. The “Parties” references the 197 countries that have ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, or the “UNFCCC” as it is known to aficionados. The Convention was first adopted at the “Rio Earth Summit” in 1992. Rio was COP1. These are also the folks behind the fabled “Paris Agreement” that came out of COP21 in 2015. If you are keeping track, 2019 is COP25, the silver anniversary.

Here’s the scoop from COP. With all the meetings and agreements and offsetting, by COP24 in 2018 we finally managed to do the unimaginable. Congratulations! We are cruising well past the 350 ppm red line set in 2008, now reaching a whopping 412 ppm of CO2. If not a new world record, it is quite a feat; it hasn’t been that high in at least a million years!

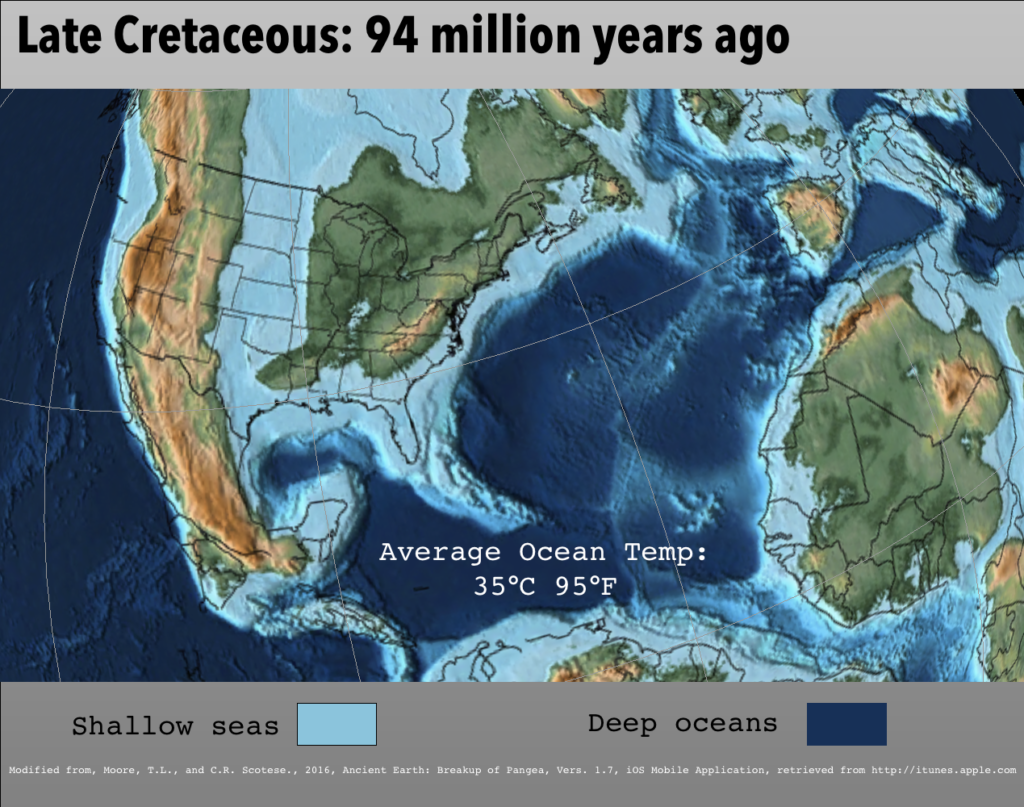

Not that this was a surprise. By the previous COP (number 23 in Bonn) it was already determined that warming less than 3°C by 2100 is no longer possible. That’s because on our present trajectory we are due to hit over 550 ppm of CO2 by 2050, and then a jaw-dropping 1,000 ppm by 2100. Hasn’t been that high in 65 million years. Welcome, ladies and gentlemen, to Cretaceous Park!

I don’t mean to be silly; it’s true, and a useful meditation. To experience conditions of CO2 at that level in the past, one would have to rub elbows with a T. Rex.

It goes without saying that in those days Adam and Eve were not yet so much as a glimmer in Gaia’s eye, probably because the goddess knew people couldn’t live in those conditions. Well, they could live, but it would have been cruel to put people in that world. Even dinosaurs struggled with it. This was a time when one preferred to be cold-blooded or a hybrid mesotherm like a leatherback turtle. Lizards and creeping things loved it, as did gigantic, massively-jawed snake-like sea creatures. Back then, much of the land mass we love was swamped in shallow, hot, briny seas. T. Rex and her kin cavorted on the shores of the slender islands which are todays continents. For us to live in a world like that would be to live as astronauts on another planet.

Look on the bright side.

A few experts still are. Or at least they want to spare us from alarm by promoting a vision of development, technology and progress. It’s an attractive package. Consider it for yourself. I suggest starting with Michael Shellenberger, who asks us to stop using the A word. We mustn’t think climate change is the Apocalypse, he urges, and we ought not scare people with the specter of human extinction.

You can read his 2007 book, Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility. Or start with this spasm of capitalistic gung-ho, in which legal scholar Jonathan H. Adler lauded Break Through as the best answer to the climate crisis. “If heeded,” wrote Adler for the Wall Street Journal, “Nordhaus and Shellenberger’s call for an optimistic outlook—embracing economic dynamism and creative potential—will surely do more for the environment than any U.N. report or Nobel Prize.” (I believe that last remark about feckless Nobel Prize winners was a dig at Al Gore, which serves to remind us that this book was written several months before the CO2 target was assessed in 2008.)

Al Gore’s opinion notwithstanding, the politics of possibility through economic development remains a strong idea. The cause of the illness can be its cure. Tech got us into this, and tech can get us out. While I applaud their confidence that in the long term the natural processes of the ecosystem will concede to human ingenuity and economics, I don’t believe it for a second. I cannot, for example, pin my hopes for redressing climate-driven declines in food production on making sure “poor nations get access to tractors, irrigation, and fertilizer….”

That’s what Shellenberger wrote in a September 2019 piece for Forbes. After twelve years, he is still looking on the bright side of a progressing civilization. “Over the last four years, my organization, Environmental Progress, has worked with some of the world’s leading climate scientists to prevent carbon emissions from rising. So far, we’ve helped prevent emissions increasing the equivalent of adding 24 million cars to the road,” explained the author.

The middle ground.

But hang on, that sounds like CO2 was reduced. Read carefully. He does not say that. The claim is that his Environmental Progress organization has helped prevent emissions that would otherwise occur. Although the tone is triumphant, if understood in the context of rising CO2 levels and a 3°C minimum temperature rise, it is very grim news. It means that with all that marvelous effort, with the 24 million cars worth of emissions blocked, CO2 still increased and is increasing.

Actually, COP24 reported that last year the rise was greater than in the previous seven years! In other words, thanks to the very good efforts of Environmental Progress and others, things could be a lot worse, but they are certainly not better. The trend, despite all that effort, is worse still and much worse than expected. That’s OK. As food runs out, I’m sure someone will explain to the sweating, starving population that they need more tractors and fertilizer. Optimism!

Now I do agree with him that there is hyperbole. The claim that there will be human extinction is absurd. And I agree that there is a middle ground between apocalypse and outright denial. I don’t agree however that it is a happy middle ground. At best, it is uncharted territory, unfamiliar to any human being who has ever lived. That middle ground will be a no-man’s land, a place of extinction for a great mass of species where yes, some technologically advanced humans might carve out a shelter for themselves and curse their optimistic ancestors. Not a happy place at all.

Roll up your sleeves.

You get the picture; global warming is a real thing and there is no silver lining. It is not just climate change either. We have other environmental problems related to sustained production of food, water scarcity and other things not directly related to warming. If that doesn’t blacken our rose colored glasses, how about the threat from the spread of weapons of mass destruction and their coupling to apocalyptic ideologies? Where is the cause for optimism here?

I don’t know, but again it emerges from the unlikeliest places. The staunchest proposals, like the Green New Deal, considered extreme by many, are still “framed as our last chance to avert catastrophe and save the planet, by way of gargantuan renewable-energy projects.” Have the believers become the deniers? “It’ll be OK—we can do this!” is what climate change agnostics used to say. Now we seem to hear it from the Left too, only as a kind of threat, “We will do it my way or extinction!”

That quote about last chances is from celebrated author Jonathon Franzen. In a recent edition of the New Yorker he wrote a plea to embrace painful reality. “Even at this late date, expressions of unrealistic hope continue to abound” he writes. “Hardly a day seems to pass without my reading that it’s time to “roll up our sleeves” and “save the planet”; that the problem of climate change can be “solved” if we summon the collective will.” His point, rightly, is that this is merely wishful thinking. It is already too late. The response of “we can do it!” is not in sync with the data.

Perhaps it is just Leibnizian passivity, a trait that hampers our species in all sorts of dire conditions. The world has gotten along so far, says our inner Leibniz, and hey, humans tread a path of steady progress, don’t they? Somehow it will come out alright. Fate surely will not leave precious humanity to its just desserts in this best of all possible worlds.

There is a deeper layer to our optimism too, based less on philosophy than on human nature itself. Our evolutionary (or created) predisposition is toward optimism. Without it we would just stay in bed, or more to the point, we would have stayed in our caves, dealing with life more or less as animals do. Optimism is the engine of human endeavor and intrinsic to creating our symbolic world of language and tools and culture. As such, optimism is not usually to our detriment. It becomes so only in specific circumstances where it effects a denial of danger.

The real and unreal.

To understand this, we must know first that our expansive optimism is manufactured as part of a virtual environment, an imagined universe in which we live. It is therefore an environmental issue from the start. Humans do not interact directly with the natural environment as other creatures do; we engage with it through mediating symbols—our language, our concepts, our tools, our discursive and recursive thoughts.

Everything for us is part of a story. The whole of our experience is like a movie. Indeed, that is why we tell stories and make movies; they are models of life itself. The lines we constantly write for our own story interpret and co-opt our experience in a production that stars “me,” a virtual person that the mind constructs. To reiterate, this is why we are not animals living in caves. It is a good thing.

So how does this virtual self regard the natural world? In short, it does so imaginatively. We have difficulty reconciling with the unmediated reality of the natural environment. This shows up clearly already in the way we relate to our bodies. It’s there in the way we talk: this is “my arm” and “my leg,” as though they were separate things which “I” own. The virtual “me” removes itself even from this slice of nature, the closest part, the part of the natural world in which the self resides. Think of the trouble we go to when we pretty it up, make it smell better, clothe its embarrassing bits and hide its animal functions. This is all a form of unreal optimism vis a vis the natural environment.

If calling it unreal is disturbing, please understand that I only mean this relatively. Reality and unreality can change places. Arguably, the psychic virtual universe we project is more real than nature itself, possibly expressed holographically in another dimension. Who knows? It might be that for humans, real life lies beyond mundane nature. This would present a problem, however, if we wish to remain corporeal members of the natural (as opposed to virtual) environment that is our home in this dimension. When our matrix-like environment cannot reckon with the natural reality that supports us physically, we face a grave danger. Surely the human race is not yet ready for a purely virtual existence.

A better place.

Allow me to illustrate further by reflecting for a moment on how this relates to death. In many respects, climate change and the collapse of the natural environment correlates with personal death. Like the effects of climate change, it is a known future without a happy ending. And it too is something we treat with optimism.

In our daily lives, death is absent from our consciousness. We only come to terms with it at the very end, when it is upon us, and then in a heavily mediated fashion. Before facing it squarely we look for miracles, be they advances in medical technology or those granted from above. Given a terminal diagnosis, medical professionals note that it is common to be met with denial and disconnection. Even the best prepared only really grapple with death fully when it has happened, and then too, in that extreme confrontation with the desert of the real, we conjure optimism.

How so? It’s simple. We redefine death according to the optimistic sense we have that our true selves are unchanging: death is a transition, she’s in a better place, he will live on in his legacy. As for the messy part, the whole thing is taken care of as quickly as possible by professionals trained to buffer us from the cold awful facts. Confronted with death, there will be a procession of symbol-referencing rituals to mediate the experience and abstract it into something that accords better with our optimism.

This is obvious, I suppose, and once more I’ll step forward to affirm that this optimism may, in terms of a different reality, be the most true understanding of all. It should be just as clear, however, that facing climate change in those terms will not do. There will be no skilled undertaker or priest to buffer the death of nature. Not that nature per se is going to die, but the nature that bore and supported Homo sapiens is surely terminal.

So what is the solution? Is pessimism an option? Do we embrace the desert of the real and give up our rosy-cheeked humanity? Is a morbid embrace of the dystopian all that’s left? I think not. What would be the point in that? Instead, we might use our creative gift and literally look outside the box, for the problem we face has to do with scale.

Unboxed.

Let me explain: within the framework of a lifetime, we can imagine, interpret and mediate our way through anything, including death, just fine. That works perfectly on that scale. But the natural environment is a thing of greater scale, far larger and longer-lived. None of us can function beyond it. If that system fails, there is no entity or being that stands outside of it who might fix it.

In the same way, our own virtual environment is larger in scale than any single part of it. It too is bigger than us. The processes of civilization that cause climate change exist far beyond the geometry of a lifetime. We might think of it as a virtual nature that arose from the collective and long-term storytelling of our species.

Virtual nature is big enough to rival nature itself. This explains how it is able to threaten it, and it explains why we feel so powerless to do anything about it. We exist within this virtual nature as surely as organisms exist in the natural world. Each of us is thereby a house divided—our corporeal being subject to one nature and our virtual selves subject to the other. We do not have the perspective or the power to change any of it from within. Except, and this is the important point, one of these natures is a collective construct of the mind. That’s the one juncture upon which we have some leverage.

Alchemy.

Exiting our virtual environment will be very difficult. First, we must face the truth. We can’t expect a miracle. We mustn’t look for something external to save us, something big enough to do what we cannot. Generally our hope is that “they will do something.” Who? The governments and members of the “Convention of Parties”? Are we looking for a technological messiah? Are we leaving it to Greta? Or is it a political twist we wait for: “Not this government but the one I voted for….”

Sorry, that’s just not going to happen. All these institutions are woven into the fabric, this is exactly why governmental attempts to regulate emissions are ineffective. Technology won’t work either; it is entropic, energy in and waste out. Any expectation of technology to advance without waste and alarming side-effects is tantamount to alchemy. Go turn some lead into gold while you’re at it.

Now, we already know that our presently contrived civilization is the cause of the climate crisis and other threats to the future (nuclear and otherwise). In that seminal 2008 study, the scientists noted explicitly that CO2 began increasing 6,000 to 8,000 years ago, in other words from the time civilization began. There is no mystery to it. The rise was due to the quickly established pattern of deforestation and intensive farming (in particular, irrigation). If there is any hope, it is to exit that paradigm.

That’s hard and maybe too much to consider. We’d rather sleep. Our passive optimism is like the slumber of carbon monoxide poisoning, torpent and painless. Do we really want to be awake? To be awake will mean the horrible gasping desperation that is carbon dioxide asphyxiation, each barren breath reminding us that there is no short cut.

Agony will shut out small-mindedness. Giving up plastic bags and eating less red meat isn’t going to do the trick. We can’t change enough as individuals to make a difference. The global system will still demand that you eat from a civilized table brought to you by the most artificial means, buy its earth-consuming products and travel in its latest resource hungry vehicles. Sure, you might say “Not me” to any of these points, but that just underscores your individual powerlessness. What any of us do as individuals will not matter. In ten years, fully aware and challenged to do something about it, the tide has not turned.

Frogs and kettles.

This is not a happy commentary. There is no point in comforting words. Wakefulness means just about everyone changing everything they do, refusing the system entirely, not just changing bits and pieces. This is an impossibility within the status quo, so it’s not a matter of activism but of shifting consciousness on a scale only once before witnessed in human evolution. It is possible that with a great gasping awakening we can lessen the damage or at least know how to live with it in coming generations. Warming began suddenly 6,000 years ago with a massive and quick change in the bent of the world system, why can’t it be reversed in just the same way?

The prescription: We do what we can—all those little things. We don’t kid ourselves that these gestures will fix the problem. We stare long and hard and deeply into the dark future, knowing we need to shake off the status quo entirely or honestly acknowledge that we are too trapped or too selfish to leave a positive legacy for the next century. Even if we cannot throw off the inexorable march of civilization against nature, we should at least leave the knowledge that we understood, we tried, we repented. Optimism in these circumstances is an insult to our grandchildren.

It will be too little, too late, but let’s not remain the proverbial frog in the kettle, the epitome of passive and blissfully wrongheaded optimism and as apt an object lesson on gradual warming as I can think of. Only in disavowing the frog’s passive optimism across the population is there a chance that the needed radical change can occur.

Bonus Content: How Kerosene Saved the Whales.

Further reading:

The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming

Cretaceous weather is better suited to some creatures than others.